The Dangerous End of the Post-WWII Monetary Order

Tariff Wars and De-Dollarization — Take Trump Seriously, Not Literally

If you focus on the noise, it becomes impossible to make sense of the chaos.

As many others have observed in trying to make sense of Trump’s rhetoric, “take Trump seriously, not literally.” And so, it’s time for a Deep Dive into the financial nuts and bolts of global trade, into why the unravelling post-WWII dollar-denominated trade regime MUST end in spite of all the noise in the news, and why everyone in the debate (from free trade libertarians to America First economic hawks) all bring valid points to the table but are also all simultaneously wrong if those points aren’t placed within a larger context.

Like the famous parable of the blind men and the elephant, everyone is arguing about the nature of the elephant without the context of the full picture, and so all are right and yet simultaneously also so very wrong.

~ ~ ~

For the past 6 weeks, the markets have lurching about in panicky swings, plunging as low as 20% below their all-time highs as Trump rolled out his new reciprocal tariff regime on “Liberation Day” (April 2nd).

The condemnations poured in from all sides.

The newspapers — all in unison — chimed in with their new favorite term, proclaiming that Trump had opened the door to market “Armageddon”.

The Democrats howled that Trump was destroying people’s retirement funds.

Senator Rand Paul mocked Trump’s push for reciprocal tariffs (and Trump’s claim that trade imbalances are evidence that other countries are ripping off the U.S.), stating that: “it’s based on a fallacy that in a trade, someone must lose. That somehow, when you trade with someone, there’s a loser — that China’s ripping you off, or that Japan is ripping you off. It’s absolutely a fallacy. Every trade that occurs in a marketplace is mutually beneficial.”

Meanwhile, Thomas Sowell focused on the danger of injecting uncertainty into the markets as Trump keeps changing the rules from one day to the next, stating that: “it’s painful to see what [sic] a ruinous decision from back in the 1920s being repeated because of the uncertainty that Trump is injecting into the markets, which causes capital investment to stall.”

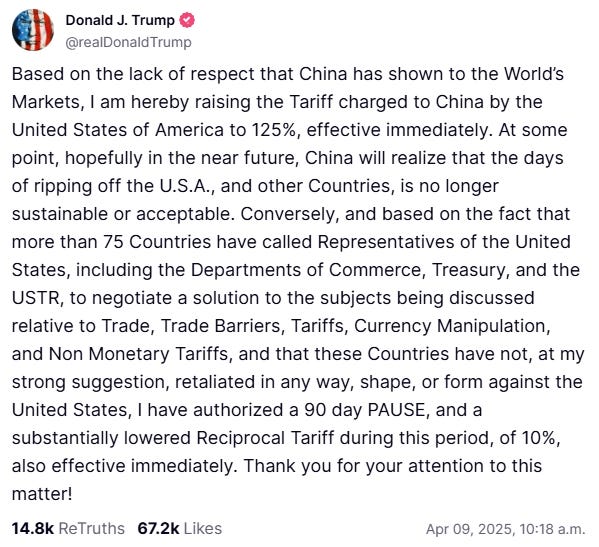

Then, only a week after “Liberation Day”, on April 9th, as the bond market showed increasing signs of panic, Trump retreated from his hard tariff stance by suddenly pivoting to provide a 90-day pause. The 75 countries that did not retaliate and instead initiated negotiations to resolve Trump’s concerns about unbalanced trade relationships saw their tariffs reduced to 10% during this 90-day pause. The media announced that market “Armageddon” had been averted.

However, belligerent Canada was excluded from that tariff reduction. And China saw its tariffs soar to 125% as punishment for its aggressive trade retaliations. Based on the rhetoric and actions coming out of China, it appears to be preparing for a full-fledged (and long) trade war.

Meanwhile, politicians in Canada were theatrically outraged at being excluded from the tariff pause, with Conservative election candidate Pierre Poilievre proclaiming, “almost every country in the world got a pause in tariffs, but not us — America’s best friend.” Of course, he left out the somewhat inconvenient point that Canada has the dubious status of being the only country in the world that joined China in retaliation against Trump’s reciprocal tariffs.

The announcement of the 90-day pause caused the stock market to surge over 10%, recovering half of the losses of the past 6 weeks in only a day. But then it settled into a narrow trading range as investors wait for cues on what will happen next. The market hates uncertainty. This was clearly just the opening salvo of what promises to be a wholescale realignment of global trade.

Democrats responded to Trumps tariff retreat with howling accusations that “this is amateur hour”, while many right-wing commentators showered Trump with praise for using this tactic to separate friend from foe and for bringing America’s reluctant friends to the negotiating table. Unfortunately, reality is far grimmer, as we shall soon see.

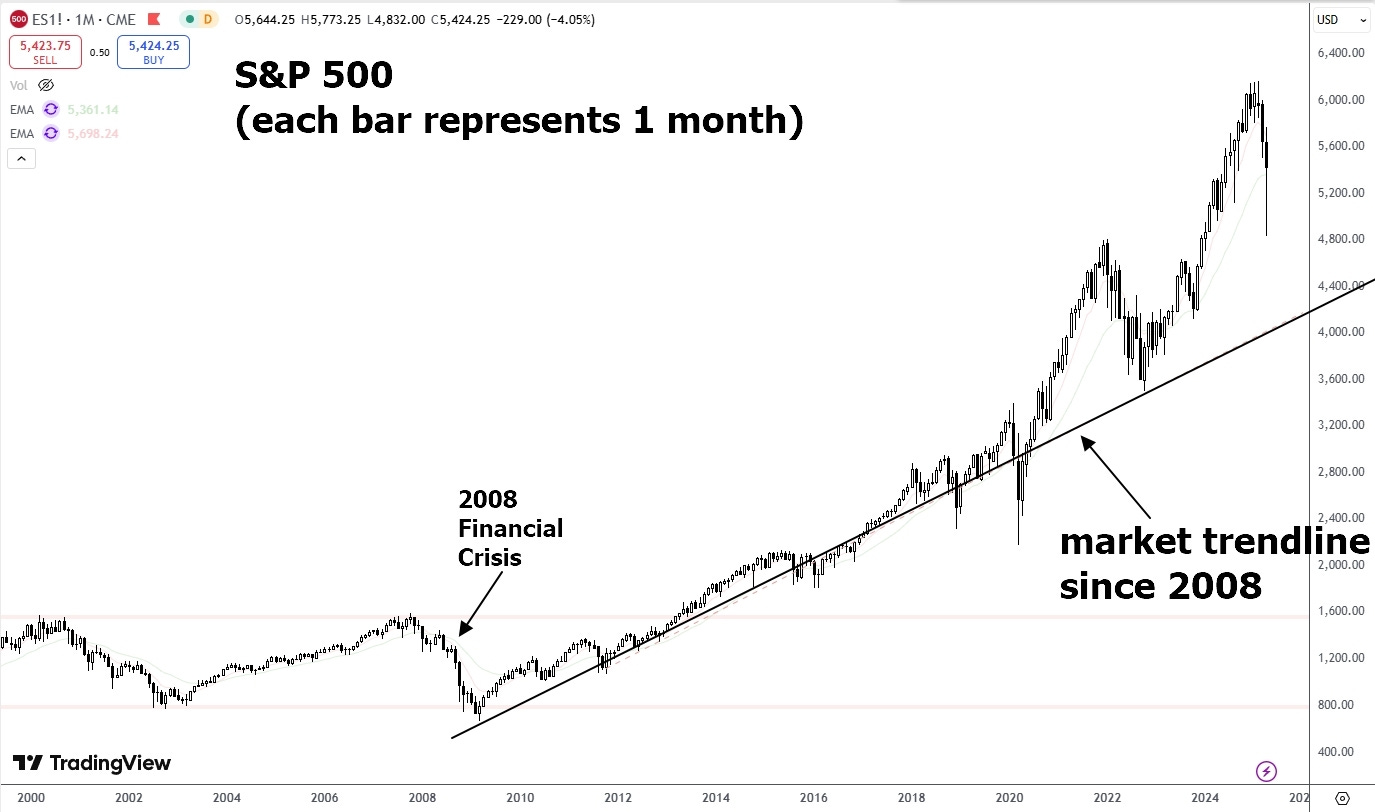

Before we dig deeper, for a little perspective I just want to show a 25-year bar chart of the S&P 500, with each bar representing one month of trading.

The chart shows how unremarkable the entire “sell-off” was — in the greater scheme of things, this was a minor market correction that took prices back to where they were in… the summer of 2024. On the chart, you can see that prices have respected a rising trendline that has been in place since the market crash in 2008. This sell-off hasn’t even come close to taking us back to that trendline, much less break it — so far, the long-term market momentum remains intact despite all the noise.

Indeed, what stands out from that long-term chart is that in 2020, during Covid, prices soared even as global economic activity was drastically curtailed by lockdowns — clearly central banks flooded the markets with vast quantities of printed money to prevent a market meltdown, which led to the rather obvious overheated market surge from 2020 to 2022 as all that printed money found its way into the stock market.

Then, as stock prices stretched ever further away from real fundamentals, the overheated market jumped on the excuse of the start of the Ukraine War to sell off again in early 2022 — stocks corrected back to the trendline, which held firm once again.

But the steep surge that followed the market correction in 2022-2023 strongly suggests that Biden’s government (and the Fed) stepped in once again to flood the market with loose monetary policies after the outbreak of the Ukraine War, which once again re-inflated a massive hyperactive market bubble that peaked in early 2025.

And, once again, Trump’s new tariff uncertainty provided investors with the perfect excuse to sell off an overheated and overbought market that had become completely detached from the underlying fundamentals. As seasoned traders will tell you, “trade the chart, not the news cycle”.

But now we’ll turn our attention to more serious matters, like the tariffs themselves and the trade imbalances that Trump keeps speaking about.

A quick Grok search reveals a strange paradox that is exposed when comparing the annualized total returns (in USD) for the U.S. stock market (S&P 500) over the past 10 years (2015–2025) versus stock market returns in Canada (TSX), China (CSI 300), and the E.U. (STPXX 600) over that same period. The United States has come out far ahead of all the others:

USA (S&P 500): ~13.8%

China (CSI 300): ~4–5%

Canada (S&P/TSX): ~6–8%

EU (STOXX 600): ~4–5%

So, the country with the best stock market returns is complaining that it is the one that’s been most badly hurt by trade imbalances while those who protect their industries with one-sided tariffs and other unfair “soft” forms of protectionism lag far behind? Something doesn’t add up.

If tariffs are the solution to America’s economic problems, why has the country with the least tariffs outperformed all the countries that have used tariffs and other soft trade barriers to protect their economies from their global competitors?

Before we let these paradoxical data points lead us astray, we have to dig a little deeper into the story. After all, stock prices are merely one small part of a much larger global financial jigsaw puzzle.

Thriftville and Squanderville

From the very start of his 2nd term, Trump has stated his intention to reform the trade regime of the post-WWII era — as Trump would say, “they’re treating us very unfairly on trade.”

As the following chart shows, the last time that the U.S. had a positive trade balance with the rest of the world was in 1975. Since then, the U.S. has consistently and increasingly bought far more stuff from the rest of the world than the rest of the world buys from the U.S. As we’ll soon see, despite the blooming U.S. stock market, these chronic trade imbalances are indeed a recipe for financial disaster.

By 2024, the U.S. had a combined trade deficit with its top 30 trade partners to the tune of a colossal $1.2 Trillion dollars per year, as shown in the chart below from Wikipedia. And that’s before we factor in the cost borne by the U.S. for essentially bankrolling the national security of all of its NATO and Asian allies.

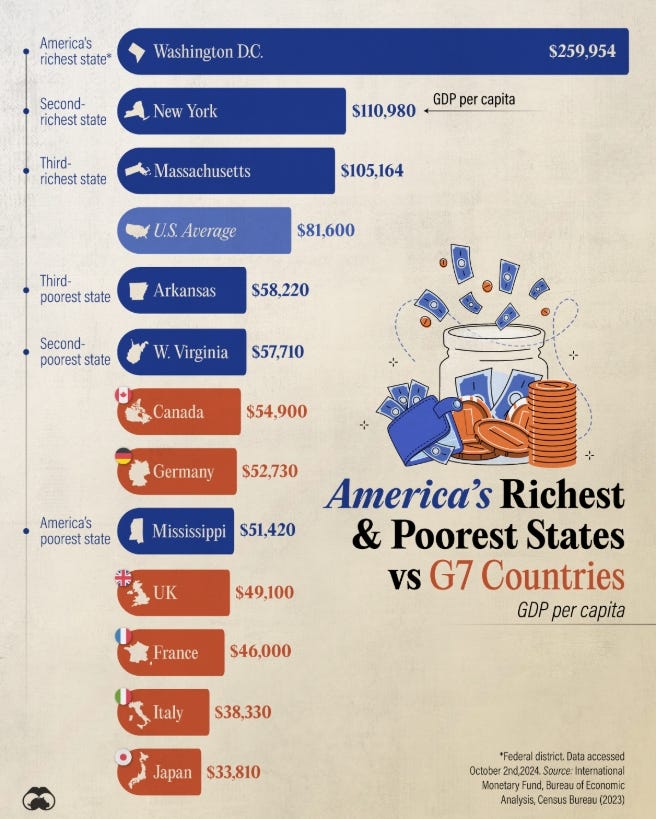

Contrary to Trump’s oversimplification of the issue, which focuses on reciprocal tariffs in an effort to fix trade imbalances on a country-by-country basis, what matters is the global trade balance. Country-by-country trade imbalances are an unrealistic measure — for example, if a country like Canada taxes its own citizens to death and hamstrings its own industry with red tape, there’s no way that we can afford to buy as much from the U.S. as they buy from us — on paper the “net benefit” of the trade imbalance is in Canada’s favor, but a quick look around Canada’s rapidly declining standard of living undermines any illusion that this leads to “winning”.

As the Visual Capitalist reported on November 18th, 2024, Canada’s GDP per capita ranks between West Virginia (America’s second poorest state) and Mississippi (America’s poorest state). That’s not “winning”. Meanwhile, despite the U.S. being on the “losing” end of that trade imbalance, they benefit tremendously from being able to buy the few things we do produce (like oil) for as cheap or cheaper than they can produce them, regardless of whether we’re buying other stuff from them in equal measure.

In his interview with Tucker Carlson, Bob Lighthizer (Trump’s U.S. Trade Representative during Trump’s first term) confirmed this — the balance of trade between two individual countries is largely meaningless; the only thing that actually matters to a country is whether there is a persistent net positive or net negative trade balance on global trade. But why? How can something that isn’t a problem on a country-by-country basis nevertheless be an existential problem when all those countries are added together? This is where the story begins to get interesting…

In his 2003 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett laid out a stark warning about the detrimental consequences of allowing these chronic trade imbalances to persist through his analogy to two fictional countries — Thriftville and Squanderville. I’ve reproduced the short story below:

“[…] our trade deficit has greatly worsened, to the point that our country’s “net worth,” so to speak, is now being transferred abroad at an alarming rate.

A perpetuation of this transfer will lead to major trouble. To understand why, take a wildly fanciful trip with me to two isolated, side-by-side islands of equal size, Squanderville and Thriftville. Land is the only capital asset on these islands, and their communities are primitive, needing only food and producing only food. Working eight hours a day, in fact, each inhabitant can produce enough food to sustain himself or herself. And for a long time that’s how things go along. On each island everybody works the prescribed eight hours a day, which means that each society is self-sufficient.

Eventually, though, the industrious citizens of Thriftville decide to do some serious saving and investing, and they start to work 16 hours a day. In this mode they continue to live off the food they produce in eight hours of work but begin exporting an equal amount to their one and only trading outlet, Squanderville.

The citizens of Squanderville are ecstatic about this turn of events, since they can now live their lives free from toil but eat as well as ever. Oh, yes, there’s a quid pro quo—but to the Squanders, it seems harmless: All that the Thrifts want in exchange for their food is Squanderbonds (which are denominated, naturally, in Squanderbucks).

Over time Thriftville accumulates an enormous amount of these bonds, which at their core represent claim checks on the future output of Squanderville. A few pundits in Squanderville smell trouble coming. They foresee that for the Squanders both to eat and to pay off—or simply service—the debt they’re piling up will eventually require them to work more than eight hours a day. But the residents of Squanderville are in no mood to listen to such doomsaying.

Meanwhile, the citizens of Thriftville begin to get nervous. Just how good, they ask, are the IOUs of a shiftless island? So the Thrifts change strategy: Though they continue to hold some bonds, they sell most of them to Squanderville residents for Squanderbucks and use the proceeds to buy Squanderville land. And eventually the Thrifts own all of Squanderville.

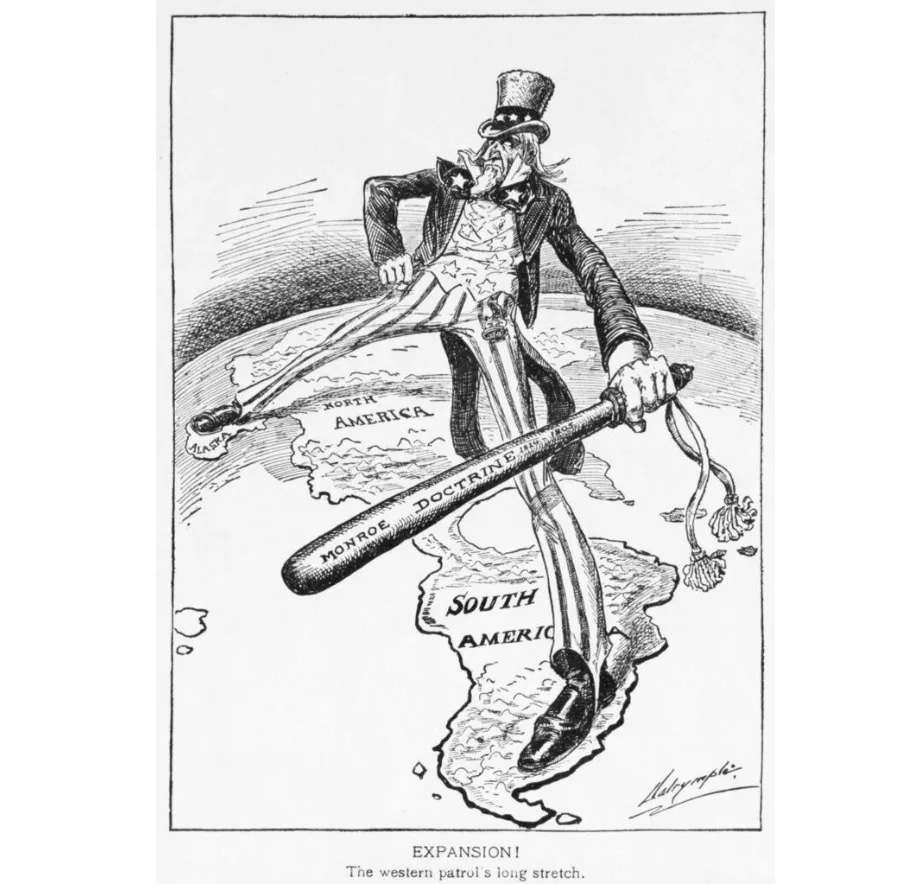

At that point, the Squanders are forced to deal with an ugly equation: They must now not only return to working eight hours a day in order to eat—they have nothing left to trade—but must also work additional hours to service their debt and pay Thriftville rent on the land so imprudently sold. In effect, Squanderville has been colonized by purchase rather than conquest. [my emphasis]

It can be argued, of course, that the present value of the future production that Squanderville must forever ship to Thriftville only equates to the production Thriftville initially gave up and that therefore both have received a fair deal. But since one generation of Squanders gets the free ride and future generations pay in perpetuity for it, there are—in economist talk—some pretty dramatic “intergenerational inequities.”

Let’s think of it in terms of a family: Imagine that I, Warren Buffett, can get the suppliers of all that I consume in my lifetime to take Buffett family IOUs that are payable, in goods and services and with interest added, by my descendants. This scenario may be viewed as effecting an even trade between the Buffett family unit and its creditors. But the generations of Buffetts following me are not likely to applaud the deal (and, heaven forbid, may even attempt to welsh on it).

Think again about those islands: Sooner or later the Squanderville government, facing ever greater payments to service debt, would decide to embrace highly inflationary policies—that is, issue more Squanderbucks to dilute the value of each. After all, the government would reason, those irritating Squanderbonds are simply claims on specific numbers of Squanderbucks, not on bucks of specific value. In short, making Squanderbucks less valuable would ease the island’s fiscal pain.

That prospect is why I, were I a resident of Thriftville, would opt for direct ownership of Squanderville land rather than bonds of the island’s government. Most governments find it much harder morally to seize foreign-owned property than they do to dilute the purchasing power of claim checks foreigners hold. Theft by stealth is preferred to theft by force.

Warren Buffett’s analogy provides a grim warning of what is happening to America. Instead of accumulating capital through savings that can be reinvested back into the economy, America is funding itself by issuing mountains of IOUs (Squanderbucks)… by selling bonds and by printing money (a.k.a. “quantitative easing”).

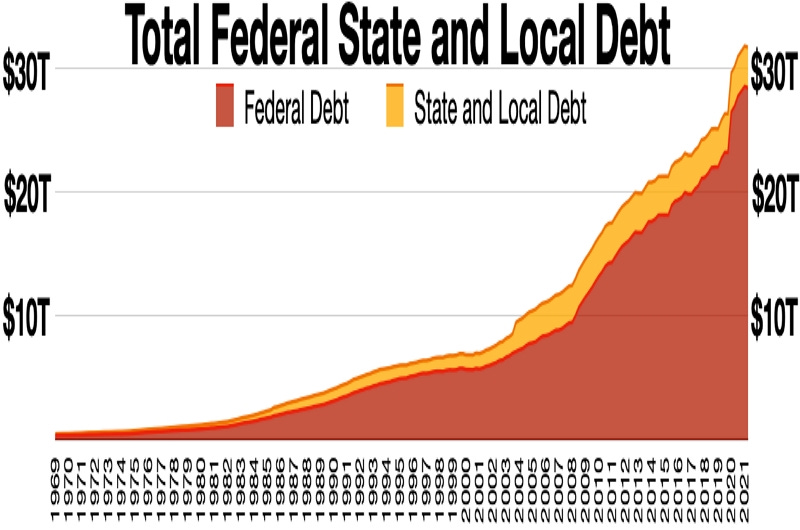

The chart below shows the amount of public and private debt that has accumulated in the United States.

Of course, there’s a limit to how much debt any business can carry without being crushed by its debts, so most of that debt is accumulating in the hands of the government (as a direct liability to taxpayers). As of today, the US National Debt is closing in on $37 Trillion — more than $323,049 per U.S. taxpayer.

This raises several questions:

To what degree is mass migration being used as a deliberate strategy to try to outrun spiraling debts in Western countries in an effort to grow their economies by growing the population? Mass migration is, above all, a desperate last-ditch economic strategy for nations that have trapped themselves in an unsustainable debt spiral. Canada has already reached the point where GDP per capita is shrinking, yet the economy is growing nonetheless (just barely) simply because Canada is using mass migration as a way to grow the economy.

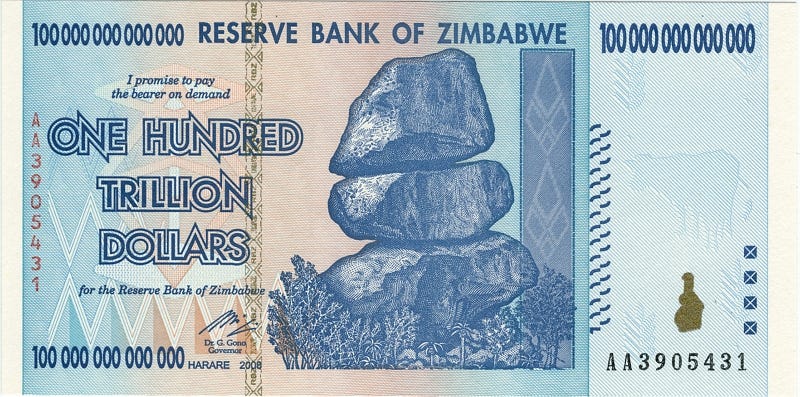

And is all that inflation that you see at the grocery store a deliberate strategy to try to “inflate” away the accumulating debt? Virtually every country in history that drowned itself in debt and got addicted to government spending has turned to this dirty trick to try to keep the party going rather than tighten its belt and face its problems, from Roman emperors “shaving” the coins (thus debasing their currencies) to the most spectacular disasters in money printing, from 1920s Weimar Germany to the early 2000s in Zimbabwe.

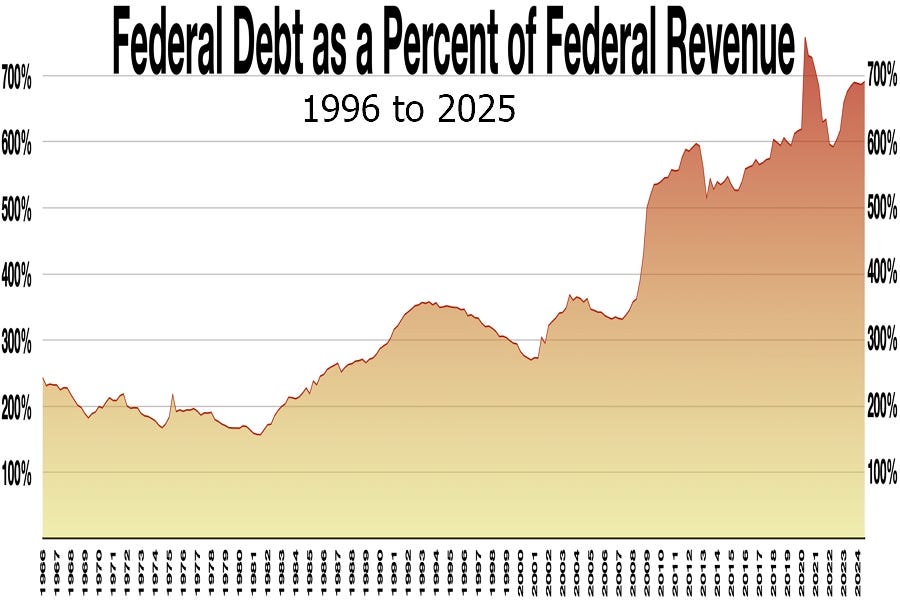

Of course, the government can only raise taxes so far before strangling the economy, so all that debt is piling up in government hands — we’ve reached the point where bonds are being issued to raise the money to pay the interest due on older bonds. As the chart below shows, federal debt as a percentage of federal revenue (i.e. tax revenue) has exploded from around 200% in the late 60s to around 700% by 2025.

If interest rates ever truly surge to reflect this increasingly risky situation (i.e. if Thriftville ever starts to worry about Squanderville’s ability to service its debts), the entire house of cards will instantly come crashing down as interest payments balloon to swallow the entire U.S. economy. As Elon Musk has indicated on X (Twitter), “the biggest threat to citizens of the United States is uncontrolled government spending creating ruinous debt.”

Furthermore, as long as the trade imbalance persists, what do foreigners do with all their excess Squanderbucks? If they’re not going to buy American goods and services to return those Squanderbucks back to American soil, they are instead going to use those Squanderbucks to invest in the U.S. stock market, buy U.S. bonds, or buy U.S. assets (farmland, real estate, ports, corporations, etc.) — and the profits from these things causes still more Squanderbucks to accumulate in foreign hands. As long as these trade imbalances continue, this has, quite literally, become a self-reinforcing system that is slowly spiralling towards an inevitable catastrophic conclusion.

A quick search on Grok suggests that, as of 2024, foreigners own an estimated:

33% of U.S. Treasuries ($8.5T),

27% of U.S. corporate bonds ($4.4T),

18% of U.S. stocks ($16.5T),

… and when considering the total value of all assets in the United States, including stocks, bonds, real estate, farmland, ports, etc., etc., though it’s hard to pin down, foreign ownership of these total assets is likely in the range of 10-15%.

To echo Warren Buffett, this is what ‘colonization by purchase rather than conquest’ looks like.

And, since every country is playing the same game, they are all locked in a perpetual currency war, collectively waged against their own people, in order to prevent their own currencies from becoming stronger than the ever-weakening U.S. dollar, which would choke off their lucrative trade relationships with the U.S. The post-WWII era may not be a chaotic hyperinflationary event like what happened in Weimar Germany or in Zimbabwe — yet — but make no mistake, this is a managed global race to the bottom...

Since President Nixon took America off the gold standard in 1971, the U.S. Dollar has lost over 98% of its purchasing power in terms of gold! Squanderville is using the printing press to try to outrun its debts.

Indeed, two of the biggest reasons why America went off the gold standard were:

1) to give itself the flexibility to print money to pay for its wants (money printing is, after all, a hidden tax for which you don’t have to ask permission from the people),

2) and to deal with the “balance of payments” issue on global trade.

“Balance of payments” sounds harmless — something dry accountants would talk about — yet it is anything but. This is EXISTENTIAL!

As long as every dollar was backed by an equivalent amount of gold, financial discipline was imposed on the government, which had to find more gold before it could print more money. This is why libertarians all want to go back to a gold-backed currency. But even the gold-backed system had a fatal flaw — global trade — because as soon as there’s a trade imbalance, the gold-backed system begins to fall apart.

Before the gold standard was broken by Nixon, every trade imbalance that left more U.S. dollars in hands of its foreign trade partners meant that if those foreign holders didn’t want to buy more American “stuff”, they could instead call in their IOUs by redeeming the equivalent dollar value in gold. In other words, instead of buying American steel, oil, or cheeseburgers with their extra dollars (at the risk of creating competition for their own domestic steel, oil or cheeseburger sellers), they could instead demand that the US government open its vaults and hand over an equivalent amount of gold.

As world trade increased in the 19th century, this dollar-for-gold exchange became a major banking issue on the world stage.

By the 1870s, a world gold standard emerged between trading nations, which allowed nations trading with each other to settle international trade and currency imbalances by shipping gold back and forth, which they regularly did — indeed, the U.S. shipped significant amounts of gold to Europe during the 1850s and 1870s on transatlantic steamships.

However, while this system imposed financial discipline on national economies, it could also be quite disruptive — severe gold outflows sometimes triggered deflation or banking crises, as seen in the U.S. during the 1890s, as outflows sucked so much gold out of the American financial system that the American economy was starved of money (for issuing loans, settling payments between companies at the national scale, etc.) How do you pay for things on the home front if there’s not enough dollars/gold left in circulation because it’s all been shipped overseas to settle trade imbalances?

The First and Second World Wars completely destroyed this gold-backed system as financial discipline evaporated. Gold outflows became so severe during WWI that the U.S. restricted gold exports to foreign countries. In 1933, during the Great Depression, the U.S. went even further by suspending convertibility between gold and the dollar. Then, in 1934, FDR banned all private gold ownership in the United States and revalued gold from $20.67/ounce to $35/ounce, thereby significantly devaluing the dollar in order to try to stabilize the shrinking economy.

This emergency monetary regime remained in place until the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944 (at the tail end of WWII), which formalized this new regime by officially making the dollar the world’s reserve currency, convertible to gold at $35/ounce for foreign institutions (but no longer for foreign individuals — they were henceforth barred from converting their dollars to gold). This new financial order was overseen by two new purpose-built international institutions — the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank — both also created in 1944. At that time, the U.S. still held around 20,000 metric tons of gold in reserve. Remember that number…

As early as the 1950s, the first cracks already began to appear in this new Bretton Woods monetary system because of persistent trade deficits, which were causing a significant drain on U.S. gold reserves, despite the fact that the U.S. had deliberately encouraged those trade deficits as an act of good will in the aftermath of WWII. These trade imbalances were designed to help the economic recovery in Europe and Japan… after all, these war-torn countries needed to buy a lot of stuff to rebuild their nations but had very little to sell to the United States since their entire manufacturing base lay in ruins. The U.S. also deliberately turned a blind eye to their protectionism because, by allowing a one-way trade flow, this would allow these impoverished war-torn nations to quickly build up financial reserves (capital) that they could then use to invest in rebuilding their economies.

There’s an important lesson here before we go on:

trade imbalances allow a nation to quickly build up large capital reserves without having to fund their growth with debt — the nation building up its capital reserves through trade surpluses is essentially funding itself with excess dollars left over from trade imbalances, which it can then use to invest back into its economy rather than having to go to the bond markets to raise capital via debt.

By the 1960s, maintaining this monetary/trade system required persistent central bank interventions and restrictions on gold redemptions as U.S. gold reserves dropped ever lower. By 1960, U.S. gold reserves had dropped to around 15,000 metric tons, despite the fact that the U.S. government was continually attempting to replenish its own gold reserves by purchasing substantial amounts of gold from its domestic gold miners throughout this period.

In desperation, the U.S. began encouraging foreign countries to hold U.S. dollar reserves instead of gold. By 1968, the official dollar-gold peg at $35/ounce was so distorted (more paper dollars than gold) that U.S. gold reserves, which had by then fallen to below 10,000 tons, only covered a fraction of outstanding dollars abroad, causing confidence in the dollar to fall.

An unofficial (black market) trade emerged (like it always does in countries with an artificial exchange rate that doesn’t reflect reality), which exchanged gold at a much higher valuation — holders of dollars had become so concerned about dwindling U.S. gold reserves that they were willing to take a major haircut on the value of their dollars in order to exchange them for gold. Speculators piled in, increasingly betting against the dollar. And countries like France and Switzerland, increasingly nervous about America’s ability to meet its dollar-for-gold obligations, began demanding large quantities of gold to be shipped across the Atlantic to cover their dollar reserves. By 1970, this drain on U.S. gold reserves caused inflation in the U.S. to hit 5.7% as unemployment surged and economic stagnation set in.

And so, in 1971, President Nixon ended the Bretton Woods era by taking the U.S. off the gold standard altogether — dollars could no longer be redeemed for gold — which allowed the U.S. to print its way out of its financial problems. From that moment onwards, the fiat U.S. dollar was backed by nothing more than the public’s trust in the government’s promise that the nation would remain solvent and wouldn’t inflate away the value of its currency via money-printing. This allowed the government to inject a massive amount of liquidity into the U.S. economy via money printing, on demand, without having to back new dollars with an equivalent amount of gold.

By the time Nixon closed the gold window, U.S. gold reserves had fallen to a mere 8,100 metric tons. Of course, with the dollar unpegged, the U.S. was now free to print money to its heart’s content. By 1980, inflation peaked at 14% in the U.S., while interest rates peaked at 20% in order to try to reign in this rampant inflation. However, with money-printing now established as the government’s go-to-tool to solve economic problems, and with a dollar untethered from gold, inflation became a deliberate stealth policy tool to inflate away debt (governments even created an official “inflation target”). Investors, stock markets, real estate owners, and those with pension funds loved it because, on paper, everything appears to be permanently going up in value, thanks to inflation, even as government can then pay for its extravagent spending promises by levying capital gains taxes on all those “fake” rising values caused by inflation, even as yesterday’s debts become easier to pay back with tomorrow’s inflated dollars.

But the trade imbalances remained nonetheless. Only now, instead of gold accumulating in foreign hands as a consequence of trade imbalances, dollars and bonds are accumulating in foreign hands. By consequence, this is leading to a steady accumulation of land, real estate, stock shares, and other assets in foreign hands. Even Nixon, despite breaking the gold standard, was fully aware of this ongoing problem — he imposed a 10% tariff on imports (similar to what Trump is trying to do today) to try to deal with these persistent trade imbalances.

The world knows the current dollar-backed monetary order isn’t working any better than Bretton Woods did. But what must be done to fix it?

Some want to return to the gold standard (and, indeed, many central banks are currently stockpiling vast quantities of gold — more on that shortly). The BRICS countries are flirting with creating a commodity-backed currency. Bitcoin has ambitious goals of creating a currency outside of the control of central banks. And Western nations are all working on some kind of digital currencies that are intended to give central planners much more leverage (carrots and sticks) over your buying and selling choices, which they hope to somehow solve their problems by being able to squeeze you hard enough to make up for irresponsible government spending and money printing. We may not yet know the shape of things to come, but everyone is taking steps to prepare for de-dollarization.

But while some of these options might, in a theoretical utopian scenario, be able to rein in out-of-control money printing and out-of-control government spending, or scratch the itch that central planners feel to give themselves even more control, none of these “solutions” addresses the underlying issue of trade imbalances, which can destroy entire nations even if the politicians and bankers play by all the rules.

And of course, everyone who benefits from the current inflationary monetary regime and the current unbalanced global trade system — investors, domestic corporations, retirement funds, home owners, bloated government payrolls, politicians who buy votes with out-of-control spending, and all the foreign nations, foreign companies, and international mega-corporations that are on the “winning” side of these unbalanced trade relationships — are all strongly motivated to preserve the status quo, even if that status quo leaves America spiralling towards an existential reckoning at some point in the future when Squanderville’s bills come due.

Trump didn’t create this mess and he’s the first president in my lifetime who’s taking a very aggressive pivot to confront it. His tool of choice to try to fix it — tariffs and trade barriers. But what he’s up against isn’t just a technical nightmare to solve, the very act of trying to solve it also risks sparking a revolution at home (and a trade war abroad) among all those who benefit from Squanderville’s debt-funded lifestyle and think it can continue without consequences forever.

The problem with centrally-planned systems is that the incentives lock the system in place, creating a self-perpetuating cycle. By the time everyone recognizes that the system is broken and is putting everyone at risk, the system itself has become so fragile and brittle, and everyone so dependent upon it, that it becomes nearly impossible to fix without risking destabilizing the entire system and plunging the nation into an existential crisis. And in the global post-WWII era in which everyone’s markets and financial systems are interconnected, any national crisis quickly spirals into a global one. As Wall Street likes to say, “when America sneezes, the world catches a cold.”

Yet, the longer that impending crisis is deferred and left unaddressed, the bigger the reckoning will be when it finally happens. Elon Musk has described America’s looming bankruptcy as a “ticking time bomb”. By pivoting to address this, Trump is hoping to engineer a soft landing.

The choice taken by generations of previous presidents of punting this problem down the road for the next president to deal with is no longer an option. Even before Trump returned to office, changes in the bond market were flashing alarm bells, signalling that the status quo of the post-WWII era were about to come to a catastrophic end as bond investors begin to lose faith in America’s ability to service its debts.

~ ~ ~

Before I dive into the second half of this essay — into the emerging bond crisis, soaring gold sales, and China’s hostile mercantilism — I want to thank all my paid subscribers for your support. It means the world to me!

If you are not already a paid subscriber, I’d like to ask for your support in the form of a paid subscription to my Substack. These kinds of essays require a colossal amount of time, effort, and research to produce. My liberty to tackle topics that others cannot comes from the fact that I am not sponsored by any think tank, media outlet, or political organization. My freedom to explore ideas and think out-of-the-box comes from the fact that I am 100% reader-supported by people like you.

But if you’re not ready to sign up for a paid subscription, perhaps you’d consider leaving me a tip in the Tip Jar on my website to help support my writing.

~ ~ ~

“At first you go bankrupt slowly, then all at once.”

A brief recap sets the stage for understanding the dangerous situation that is developing in the bond markets: