How do you de-program a mind that has succumbed to ideology, mass hysteria, or propaganda?

And how do you fix an entire society once the “cult” goes mainstream?

~ ~ ~

Before we turn to the unpleasant business of population-scale deprogramming, I want to begin with a revealing story about a repulsive yet pitiable old man that I briefly stumbled across many years ago who had so firmly fused his identity to a radical ideology during his formative years that, even decades after his peers had all moved on, he spent the rest of his unhappy and isolated life trapped inside that ideology to shield himself from the psychological void of having to sever his identity from those beliefs.

~ ~ ~

Fresh out of high school in the early 1990s, I spent several months apprenticing on a cattle ranch in Namibia. On one occasion, my host invited me to join him on a drive to another distant Namibian farm to deliver a piece of machinery. It was a beautiful drive and a chance to see more of Namibia’s stark and harsh Kalahari beauty.

By that time, SWAPO’s guerilla war against the South African government was over, Namibia had gained independence from South Africa (in 1990), and South Africa’s withdrawal marked the end of apartheid in Namibia. A cautiously hopeful and reconciliatory mood had replaced the fear and repression of the previous era.

And yet, in marked contrast with everywhere else that I travelled across Namibia, driving onto that distant Namibian farm was like stepping into another world.

We arrived at nightfall. Driving into the dusty farm compound, we were surrounded by razor-wire fences, stern armed guards, and a snarling mass of rottweilers. And it was all lit up by massive flood lights mounted all along the tops of the fence posts. This Namibian farmer lived in perpetual fear.

While that heavily fortified compound might be normal today in the dangerous failing state of South Africa, the contrast with the rest of the society I encountered in Namibia in the early 1990s was so stark that I made some brief comment about it to my host as we drove in. He acknowledged that this old farmer was “a little off in the head”. And then, before jumping out of the truck to sort out the machinery, he wryly remarked, “things are even more strange inside his house — he still has a giant WWII-era Nazi flag hanging on his wall.”

… wait, what!?! 👀 And why are you even doing business with a guy like that?!?

On our drive back to the home ranch, my host went on to tell the full story of this old Namibian farmer and the circumstances that had shaped his broken mind, which I have fleshed out below with a little extra context from that era. As always, history and psychology are deeply intertwined. There is nothing random about why minds are captured by ideology or succumb to propaganda or hysteria — history creates the circumstances; human nature does the rest.

~ ~ ~

As World War I broke out, South Africa (then still a part of the British Empire), invaded and seized the neighboring German colony of Namibia (then called German South West Africa). In truth, it wasn’t much of a fight — the Kaiser had more pressing wartime concerns to attend to than a distant colony that perpetually cost his empire more money than it generated. German settlers were summarily interned in an abandoned military fort near Pietermaritzburg until the end of the war to keep them from making any trouble.

After WWI ended, the League of Nations gave South Africa a mandate to continue to administer Namibia, effectively turning the former German colony into a de facto fifth province of British South Africa.

Its German-descendant population was NOT happy about its new circumstances and resisted cultural assimilation, feeling that their Germanness was threatened, although that resistance never grew beyond cultural resistance — it never escallated to become an organized resistance movement. German-language schools and organizations sprouted everywhere to try to preserve their German cultural identity as a kind of counter-reaction against the encroachment of British and Boer culture. But beyond that, the German settlers seamlessly integrated into South Africa’s political system and even participated in both local administration and the South African parliament, though they continued to yearn for some kind of German-led political control or even to return their beloved South West Africa back to Germany. This is the cultural backdrop in which our old German-descendant Namibian farmer grew up.

When World War II broke out in September of 1939, the Union of South Africa (as it was then called, as a self-governing dominion within the British Empire), initially deliberated whether to stay neutral given the divided loyalties of its society. But then, only a few days into the war, it too decided to declare war on Germany and once again began rounding up citizens of German descent (mostly the men), which were reclassified as “enemy aliens” — especially in the former German colony of Namibia (South West Africa). Around 5,000 German men (out of a total population of around 33,000 to 40,000 Germans) were interned.

What happened next inside these internment camps is crucial to understanding this old Namibian farmer’s story. For context, most other allied Western countries behaved similarly. The United States, for example, rounded up 120,000 Japanese Americans and 11,000 German Americans and placed them in internment camps for the duration of WWII (just in case, even if they displayed no signs of divided loyalties and were fully assimilated into American society). Likewise, the UK interned around 30,000 “enemy aliens”. Australia interned around 7,000.

Even Canada interned around 24,000 “enemy aliens” in 24 separate camps spread out across the country, with a particular focus on Japanese Canadians, German Canadians, Italian Canadians, Ukrainian Canadians, and, rather bizarrely, 2,284 Jewish refugees who arrived by boat from Germany, Austria, and Italy to escape persecution (and worse) — these refugees were also classified as “enemy aliens” and were treated with the same suspicion as all the other internees because they originated in countries with which Canada now found itself at war.

In Canada’s case, the Canadian government finally apologized to Japanese Canadian internees, reinstated their citizenship, and offered them financial compensation to the tune of $21,000 each… in 1988…, one month after Ronald Reagan did the same for Japanese American internees. In neither country was this gesture extended to inlude Germans, Italians, and others who were also interned during the war.

Conditions inside these internment camps, from South Africa to Canada and beyond, were far from ideal. One of Canada’s biggest internment camps was right here in Vernon, British Columbia, not far from my home today. The national director of Canada’s internment program described Vernon as being “the most difficult of camps”, with harsh and unsanitary conditions, severe overcrowding (one building designed for around 80 people housed more than 500), forced labour (in construction, agriculture, roadwork, etc.,), and with severe punishments meted out to internees, including solitary confinement. It all amounted to a harsh, indefinite, and extralegal prison sentence, but without trial, without a legal process, and without individual charges.

Affected families designated as “enemy aliens” by the bureaucratic machine had their homes, farms, businesses, and property seized, and faced financial ruin and stigmatization. Families were typically separated, with men sent to different camps than the women and children. Some families were never successfully reunited. South Africa was actually one of the few British territories that allowed women and children of interned men to remain free instead of shuffling them off to separate family camps.

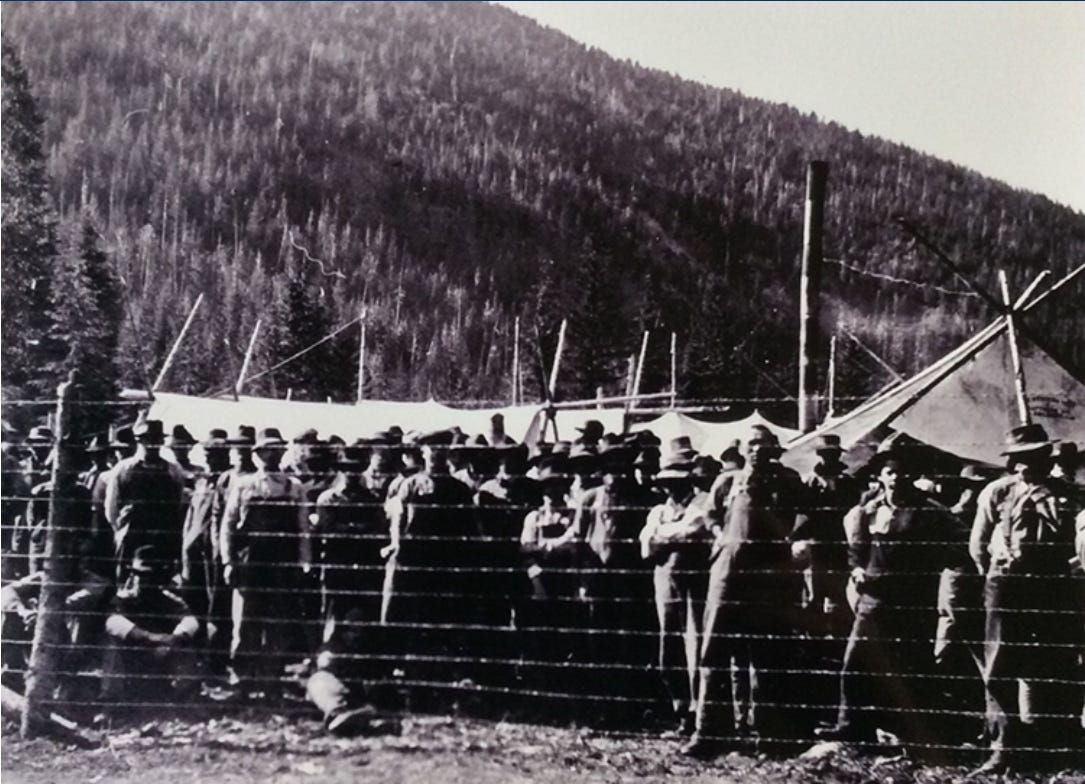

Nor was WWII internment unprecedented. For example, during WWI, Canada interned around 8,579 “enemy aliens” (primarily German Canadians, Ukrainian Canadians, and other immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Bulgarian empires.) The WWI-era Monashee Mountain internment camp (which was located just an hour and a half from where I live today) was opportunistically used by the Canadian government as a forced labor camp to build a much needed road over the rugged Monashee Pass (Highway 6), with appalling conditions for the inmates (see image below).

Many affected families struggled for a long time to reconcile their Canadian identity against the persecution, injustice, and stigmatization that they faced during those years — the Vancouver Sun even went as far as to encourage German-born residents to change their names to disguise their German heritage.

My point in explaining all this context is that the experiences that our Namibian farmer went through inside those camps undoubtedly felt unfair, but they were also not unique, and yet he came out permanently radicalized even as most other internees did not. In fact, South Africa’s camps were unusually lenient compared to internment camps in other Allied countries and yet, paradoxically, they were also unusual for the extreme radicalization that happened inside those internment camps, as will become apparent in a moment. In many ways, what happened inside those South African internment camps is a real-life version of the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, except in this case it was the inmates themselves that were self-administering much of life inside the camps, and driving both the abuse and the radicalization inside this perverse echo chamber, even as the authorities did little to stop it. But I’m getting ahead of the story.

A 2024 research paper describes the prelude that led to internment in South Africa. In the lead-up to WWII, many Germans living in South Africa and Namibia:

“enthusiastically greeted Hitler’s rise to power as the beginning of a new dawn for their mother country after a humiliating defeat in the First World War. […] While there was a broad consensus amongst them that Hitler was inducting Germany’s rebirth, the haughty claim of a younger generation that the Nazi movement was the sole representative of German interests in southern Africa clashed with older conservative traditions. Monarchist nostalgia was still prevalent in sections of the German community. The modest numbers of card-carrying members of the Nazi party in the Union of South Africa reflected the integration of Germans into socio-economic networks dominated by white English-speakers, which mitigated against noisy declarations of support for Hitler. [my emphasis]” (Dedering, T., 2024)

In other words, while support for Germany was high in South Africa’s German community, the entire German population was also not a uniform and frothing mass of rabid Nazi fanatics either. Nonetheless, support for both Germany and the Nazi movement was greatest in South West Africa, whose German-speaking population was unhappy to have been stripped of its own government after WWI and was grating under British South African rule and the pressure this placed on the continuity of their German culture.

South Africa’s fear that these Germans might become a fifth column to sabotage and destabilize South Africa during the war were thus not entirely unfounded — even Hitler’s foreign branch was known to have been working behind the scenes in the region. However, it’s also worth noting that pro-German sentiments were separate from the much larger and more actively pro-Nazi Afrikaner nationalist movement that was also rising in South Africa at that time (the Afrikaner Ossewabrandwag organization is estimated to have had around 350,000 members at its peak in 1941, out of a total white population of only 2,073,000 !). There certainly was some overlap between German and pro-Nazi Afrikaner views and political membership (especially among the younger German population), much to the concern of South Africa’s British government, but reality was nonetheless nuanced — something to bear in mind as we see what happened next inside these internment camps. However, in the heated atmosphere on the eve of WWII, rumors of German conspiracies were spreading like wildfire.

When the war broke out, tensions between pro-German and anti-German factions of South African society boiled over as anti-German riots broke out in Johannesburg. Crowds hurled tear gas at Johannesburg’s German Club and German shops were attacked across the city. Within weeks, the internment camps were filling up with German men rounded up from across South Africa.

Early estimates that around 1,000 German “enemy aliens” would need to be interned quickly spiralled to 4,000 — by war’s end, a total of 6,636 civilians had been interned in six different camps across South Africa. Nor were German “enemy aliens” the only ones interned – pro-Nazi Afrikaners, anti-Nazi Communists, political dissidents, trade unionists, and anti-war pacifists also found their way into these internment camps. The Afrikaner nationalist movement accused the South African government of using internment as a deliberate ploy to lock up its political opponents — the few thousand Afrikaners who got locked up even included future South African prime minister John Vorster for his involvement with the pro-Nazi Ossewabrandwag organization.

In that heated atmosphere, even some Englishmen who were suspected of harboring German sympathies found their way into the camps. One Englishman was indicted on evidence that he “spoke German fluently”, “conducted himself like a German, whatever that meant”, and that “his diet consisted mainly of potatoes and pork”. Both justifiable fears and hysterical rumors of “Hun intrigue” all began to blur together.

It's worth noting that South Africa did not have the balls to lock up the bulk of the much larger pro-Nazi Afrikaner nationalist movement, despite the fact that they were demonstrably more actively pro-Nazi than South Africa’s Germany community. By focusing only on Afrikaner leaders, the South African government sent a clear message but avoided sparking a much bigger backlash from the Afrikaner community, which solidly outnumbered the rest of the combined white South African community (based on the 1936 Census, Afrikaners represented approximately 58% of the white South African population, compared to Germans which came in at less than 1%).

British South Africa was walking on eggshells because the Afrikaner community vividly remembered the horrors and deaths inflicted on their family members in the concentration camps run by the British during the Boer Wars only 40 years earlier (thus in living memory), which had been deliberately used by the British to break the will of the Boer resistance. South Africa’s lenience and careful attention to ensuring good conditions inside the WWII camps undoubtedly was shaped by that history and the fear of triggering a wholescale uprising among the Afrikaner community. The tiny, less organized, and less radicalized German community was much easier to control (and much easier to use to set an example), but in doing so South Africa also fueled a sense among the German community that they were being unfairly singled out.

Conditions in South Africa’s camps seem to have been remarkably good — and extraordinarily lenient — compared to internment camps elsewhere in Allied countries. Reports highlight abundant food, access to books, and there’s even mention of some camps including tennis courts and in one case even a three-hole golf course to help internees pass the time.

Furthermore, unusually, much of life inside the camps was self-administrated by the internees themselves. And in the latter half of the war, many of the less hardened internees were released back into South African society, albeit with some restrictions, rather than holding them all until the end of the war as happened in other countries. In fact, in the famous story of the two German geologists, Henno Martin and Hermann Korn, who fled into the Namib Desert to hide in the labyrinth of canyons along the Kuiseb River for two years to avoid internment, when they finally turned themselves in order to seek medical treatment for Hermann Korn, who had become desperately ill, they were given a small fine (paid by friends), released, and then hired by the government to conduct groundwater exploration even as the war raged on. Their hideout in the Canyon is now a famous Namibian tourist attraction.

But reports on conditions inside South Africa’s internment camps emphasize that rounding up and segregating radicals from society and lumping them all together inside these camps, and then giving them free rein to administer themselves, created an echo chamber that only fueled both their zeal and their sense of being oppressed, even as camp administrators allowed Nazi symbols and camp-level Nazi events and organizations to flourish inside the camps — inside some camps, “the picture of the Führer and the swastika decorated every room” and it was common for inmates in the camps to greet companions by “bellowing ‘Heil Hitler’”, though it’s not clear how many did so out of conviction versus doing so to avoid intimidation from their fellow inmates.*

As Tilman Dedering reported in his 2024 research paper, one internee at the Andalusia camp in South Africa stated that on arrival the commandant welcomed him by saying:

They are all Nazis in this Camp. If you happen not to be a Nazi yourself you will have to behave like one. If you don’t, I cannot guarantee your personal safety once you are inside the camp. Yes, you will have to give the Nazi salute. If you wish to express any views about the war they will have to be the German views, even if your views as a South African should differ.

South Africa confined both pro-Nazi and anti-Nazi inmates in the same camps, which led to significant violence and persecution against the anti-Nazi minority at the hands of an increasingly sadistic self-radicalizing pro-Nazi majority. Dissenters faced intense pressure to conform and join in with Nazi ideology.

And then Jewish refugees fleeing Europe also began to show up in South Africa. Once again, much like the approach taken by Canada, South Africa merely categorized them by point of origin, ignoring the reason for their flight from Europe, and locked them up inside the same camps. Predictably, pro-Nazi internees unleashed Hell against these unfortunate souls. Yet, camp administrators turned a blind eye to the violence being dished out by the pro-Nazi factions against both Jewish and anti-Nazi internees. Reading about it, I’m left with the impression of something not entirely unlike the story told by The Lord of the Flies, or, for that matter, the campus of a modern university.

In effect, South Africa took a population that already viewed themselves as oppressed and whose circumstances already predisposed many to view Germany’s Nazi movement as an escape from their own local troubles, and then separated off the most ideological members of that society and locked them up together, in isolation, inside an echo chamber, and nursing grievances of unfair persecution, while giving them relatively free rein inside those camps and plenty of victims upon which to vent their extreme views. Talk about pouring gasoline on an ideological fire.

This is literally the opposite of what it takes to de-fuse a cult and deradicalize a population.

Canada’s internees also included pro-German and anti-German internees and Jewish refugees, but at least Canada had the good sense to house pro-Nazi internees separately from everyone else… and subject them to re-education and de-Nazification programs rather than giving them free rein inside the camps as happened in South Africa. South Africa’s approach inadvertently created a self-radicalizing echo chamber inside those internment camps, which undoubtedly played a significant role in shaping and hardening the mind of our old Namibian farmer during his most formative young adult years. Consequently, his identity had become fused not only to those beliefs, but also to the sense of victimhood that fueled those beliefs. Like wokeism today on both the left and the right, Nazism was, at its core, fueled by victimhood culture. In his youth, our old Namibian farmer had swallowed the bait, hook, line, and sinker. And now he was trapped by those beliefs.

Ironically, once those beliefs had taken root, only being exposed to British news reporting of the war during those long years inside the camps — media that belonged to the very same side that now held him in captivity — only reinforced the impression that all the details of Germany’s crimes playing out in the news were merely British propaganda designed to discredit “his side.”

After the war when the internees were released back into society, he couldn’t move on from his radical beliefs because he’d built a psychological identity for himself based on those beliefs into which he’d poured all his own grievances. Reconciling the disconnect between what he’d come to believe about Hitler’s utopian promises and the hellish reality of how things played out under national socialism inside Germany were simply a bridge too far.

My host pointed out that this old farmer completely denied all of Nazi Germany’s crimes — he was a full-fledged Holocaust denier — to acknowledge these things would have collapsed his entire identity and the foundation upon which he’d built both his world view and his view of himself.

Instead, he retreated into the echo chamber inside his head — bitter, resentful, fearful, and fiercely in denial of anything that conflicted with both his sense of victimhood and the utopian belief system upon which he’d constructed his identity. Other than the usual interactions that take place within a farming community — equipment sales, machinery repairs, harvest sales, and fighting bushfires alongside his neighbors, he didn’t mix much with the broader community. He could have rejoined the human race at any time — the door to the rest of his community remained open — the decision to continue to isolate himself and retreat into resentment and fear was his alone. And yet, to choose otherwise would have triggered a wholescale identity crisis — that was a psychological bridge too far.

My host explained that most people in the farming community viewed him with a mixture of pity and curiosity as time left his broken mind ever further behind. As the old saying goes, “you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.”

What percentage of former internees continued to harbor similar radical beliefs is hard to say but it is clear that most moved on (or disguised those beliefs in order to adapt to post-WWII realities) — either way, our unapologetic and beleaguered old Namibian farmer was clearly the exception to the rule.

Understanding his psychological journey and why his mind remained trapped in ideological victimhood is perhaps the easier question to understand. The more difficult question is why he was the exception, not the rule.

Before I dive into the remainder of this essay, in which I explore the psychological surrender that must happen in order to cause a radicalized population to turn its back on its former ideology, I want to thank all my paid subscribers for your support. It means the world to me!

If you are not already a paid subscriber, I’d like to ask for your support in the form of a paid subscription to my Substack. These kinds of essays require a colossal amount of time, effort, and research to produce. My freedom to explore ideas and think out-of-the-box comes from the fact that I am 100% reader-supported by people like you.

And if you’re not quite ready to sign up for a paid subscription, perhaps you’d consider leaving me a tip in the Tip Jar on my website to help support my writing.

Studies of extremist groups, cults, terror organizations, and the Nazi Party’s fanatic supporters in Germany (beyond mere voters), suggest that no more than 10 to 15% of people become what Eric Hoffer called “true believers” — they make the most noise, but they never make up more than a tiny percentage of overall society. In his 1951 book The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (Amazon affiliate link), Hoffer suggested that this radical commitment to the cause is driven by personal frustrations, a sense of alienation, or a desire for purpose and belonging. Most true believers will take those beliefs with them to the grave once those beliefs have fused themselves to their sense of identity. Once in, they simply cannot find their way back out — nor do they want to.