Regardless of whether leadership is elected, appointed, inherited, or seized by a coup, all political power ultimately depends on entangled threads of patronage that grow up underneath that political power, fueled by mutual obligation and self-interest. And as it grows, it begins to warp the minds of all those who get caught up in its net.

During the Roman Era, their entire political system revolved around elaborate patronage networks in which political support was openly exchanged for preferential access to resources, benefits, or favors. They didn’t even try to hide it — the Roman patron-client relationship was a formal and visible social structure that influenced elections, judicial decisions, and economic outcomes.

It was so deeply embedded in society and so openly practiced that Romans had a well-established daily morning ritual, called the salutatio, in which clients visited their patrons every morning to greet them and request favors. Power was easily measurable simply by watching who showed up on someone else’s door — it was a brutal, efficient, and a refreshingly honest way of practicing corruption. Until the 2nd century BC, even voting was done out in the open for all to see (no secret ballots) to allow patrons to verify whether their “investments” into their clients were paying off at the ballot box.

The feudal system that emerged in Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire evolved from this Roman system, with liege lords, vassals, and serfs bound together via mutual oaths and formal hereditary legal obligations. Indeed, various waves of increasingly formal legislation passed during the late Western Roman Empire (under Diocletian, Constantine the Great, Theodosius, Valentinian, and Justinian) imposed successively greater restrictions on mobility, began binding tenant farmers (coloni) to their land, and made their legal status hereditary. These increasingly restrictive laws were all passed in response to labor shortages and the need to maintain tax revenues and food supplies as Rome shifted away from a slave-based economy to a tenant farm economy — these late-Roman legal reforms later evolved as the legal precedent for feudal serfdom in medieval Europe after the Western Roman Empire collapsed.

Whereas the Roman patronage system was based mostly on customs and traditions, the feudal manor system left less to chance — they formalized their patronage system with clear laws. They also expanded it to include church tithes, which were absent in Roman law, thereby formally embedding the Church in the State’s political patronage system. Financial dependency and political loyalty are inextricably linked — the leash may be invisible, but that doesn’t make its effect any less powerful on the mind.

And, much like what’s happening under wokeism today, while those within the feudal patronage system were in constant competition with one another for prestige, power, and privilege, they nonetheless were highly cooperative in banding together to put down any peasant revolt that emerged to try to overthrow the system as a whole — the famous German Peasants’ War in the 16th century (the largest and deadliest social revolt in Europe prior to the French Revolution) was notable for how the legions of local lords, which had essentially been at war with one another for nearly a millennia, managed to put aside their differences long enough to protect the patronage system as a whole by brutally suppressing the poorly armed peasants who demanded an end to serfdom, slaughtering hundreds of thousands.

However, the collaboration required to suppress this German Peasants’ War exposed the fragility of the decentralized feudal structure and bolstered the authority of local princes at the expense of lesser lords and knights — in time this shift concentrated ever more power in the hands of regional rulers and eventually led to the rise of powerful centrally-controlled monarchies. The patronage system not only adapts to changing political circumstances but even drives those political changes as the patronage system re-orders itself to adapt to new challenges that emerge to threaten the patronage system. As one form of the patronage system proved less useful, another emerged to replace it. It would seem that the leash created by participation in the patronage system cuts in both directions.

As power was concentrated in the hands of centralized monarchy, the character of the patronage system evolved once again to become less formal and more flexible, involving payments, pensions, and gifts in exchange for political and military support. And as monarchy continued to evolve to gain ever more power concentrated at the very top of the political hierarchy, this ushed in the Age of Absolutism, in which monarchs held absolute power, unconstrained by other institutions like legislatures or the Church. The patronage system evolved right along with it.

This led to the absurd picture of life at the court of France’s Sun King (Louis XIV) during the second half of the 17th and first decades of the 18th centuries, which I described in my book, Plunderers of the Earth (Amazon Affiliate Link):

On any given day there were anywhere between 3,000 and 10,000 nobles of greater and lesser status living in the guest rooms at the Palace of Versailles, all vying for influence with the king. Since virtually everything depended on the whims of their king, practically the whole of French nobility permanently resided at the Palace of Versailles, out of necessity, in order earn (and maintain) the favor of their king.

It was a never-ending game of jockeying played out in the courts, luxurious gardens, and between the sheets of Versailles’ more than 2,300 rooms, where even a trip home to visit your estate could spell catastrophe if, in your absence, someone else managed to catch the king’s eye and convince him to transfer your titles, privileges, or estates to someone more deserving.

In refusing to grant favours asked for by some noble, Louis XIV habitually remarked, "We never see him", meaning that the hopeful claimant did not spend enough time playing the game at the Palace of Versailles. It's a snapshot of life in a golden birdcage, where the pomp, prestige, and never-ending theatrics are a thin veneer disguising lives trapped in a golden cage.

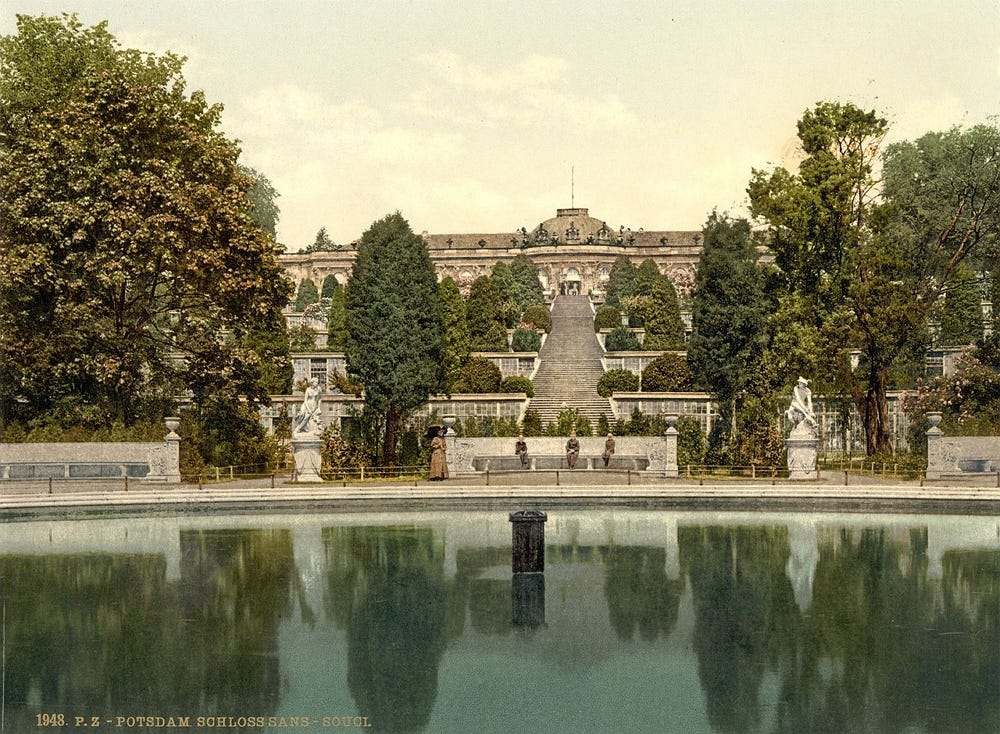

If you visit Berlin today, you can tour Sanssouci Palace, the opulent former summer palace of Frederick the Great, King of Prussia — on the tour they describe how the morning salutation had once again been resurrected (similar yet different from the Roman salutatio). Every morning, half the court lined up to visit the king’s bed chambers to greet him upon waking up, with a formal hierarchy established as to who could stand where (proximity was directly related to political connectedness in the power hierarchy) and in what order they could greet the king. Obviously, a never-ending game of intrigue was played among the courtiers as they jostled for position.

Even the job of the person managing the king’s chamber pot and wiping his bottom was a highly sought out and socially respected position, open only to those belonging to the aristocratic landowner class, as the position offered great influence and opportunities for promotion because it placed him closest to the king’s ear. And yes, in case you’re wondering, all this happened in front of the audience of privileged courtiers who attended the morning salutation — it was all part of the ritual of the court 😳 — which shows just how absurd and illogical things can get in order to cater to that all-important patronage network. If you think what’s happening in society today is because society has lost its mind, think again — you’re not viewing these phenomena through the lens of the patronage network.

In England, this highly sought-out position in charge of the king’s chamber pot became formally known as the Groom of the Stool — through the Groom of the Stool’s intimate conversations with the king and the access to secrets and influence that this placed in his hand, this position led to him becoming one of the most feared, respected, and powerful figures within the court. As Wikipedia points out, by the time of Henry VII, the Groom of the Stool had evolved into a powerful official involved in setting national fiscal policy under the “chamber system”. Talk about multi-tasking!

With the emergence of liberal democracy, which was supposed to dismantle this hierarchical hereditary system and replace it with purely democratic decision-making, meritocratic institutional promotions, and transparent government contracts, the patronage system evolved new informal ways of adapting to this new environment, with loyal supporters somehow always gaining preferential access to positions in ministries, agencies, or advisory roles, and with politicians learning how to appeal directly to voters, implicitly or explicitly, in a quid-pro-quo system that exchanges favors for votes — known as clientelistic democracy. The checks and balances we thought we’d placed on democracy in order to keep it small and honest never stood a chance.

This is why rotten, corrupt, tyrannical, or dysfunctional democratic systems, from Zimbabwe to Canada and beyond, are impossible to dislodge — once a coalition of loyal supporters is built, that patronage system, enabled by nudges, winks, and back-room negotiations, and lubricated by generous showerings of tax dollars and regulatory privileges, ensures that financial self-interest maintains a core, regime-friendly, loyal support base inside the institutions and at the polls, irrespective of how destructive that regime is to the greater whole of the country. I vividly remember, at the very beginning of Covid, as the federal government began rolling out mask mandates and business closures, it also granted all federal employees a massive raise and pay bonus. Compliance and loyalty are bought, quid-pro-quo.

Voters aren’t stupid, they’re self-interested — they vote to preserve the patronage network upon which they have come to depend. In socialist Canada, where more than 1 in 4 employed Canadians works for one of the levels of government and where 44% of every dollar that is spent in the country is spent directly by the government (rising to 64% if you include indirect spending triggered by subsidies, regulatory privileges, or coercive regulations), it’s not hard to see why the broken system is nonetheless as stable as a rock no matter how illogical it all looks from the outside. Once someone becomes dependent in some way upon a politically-managed system, it’s very hard to let go and vote against your own self interest. And so, stability is bought and paid for — peasant revolts at the polls and in the streets stand no chance against such a firmly-rooted, self-defensive patronage system.

The feudal system, despite its obvious abuses and innovation-stifling characteristics, lasted between 700 and 1,000 years (depending on which country you look at) because the web of people in whose hands power was distributed were sufficiently motivated to fight to preserve it no matter the price paid by everyone else. All democracy has done today is re-order who gets to participate in the patronage networks underpinning political and institutional power — but once a stable coalition of dependent and loyal supporters emerges, it is no less resistant to change as long as the practice of voting at the ballot box is maintained.

Nor is all the self-interest financial — power, prestige, and even emotional ties all play a role in building out a cohesive and loyal network of supporters. It’s impossible to understand the longevity of the Liberal regime, begun under Justin Trudeau and now continuing under Mark Carney, without understanding the patronage network underpinning their support at the polls — if logic, integrity, policy outcomes, fiscal accountability, or anything resembling the “greater good” were what made Canadian democracy work, the country would long since have devolved into open revolt.

No-one rules alone. Every government position, every judicial appointment, every government contract, every legal cartel (like Canada’s telecom, egg, chicken, and dairy cartels), every welfare program, every regulatory privilege, and every policy that leads to coerced spending (like electric vehicle mandates, vaccine requirements, and building codes) all add up to create a large loyal support base, based on self-interest, which defends the existing power structure against rivals and reformers who threaten to upset or embarrass the status quo.

At least the slimy Roman patron-client relationship came by its corruption honestly, whereas we have to find ways to pretend to ourselves that our self-interest isn’t playing a role in warping our choices. That’s the thing about the patronage network — it may pay handsome dividends in terms of money and opportunities, but the price paid is the loss of our independent minds — it’s to wake up one day to realize that your body, mind, and soul are now being bent in servitude to an invisible leash. Sure, you could walk away from it all in a heartbeat and no-one would stop you, but would you want to? What price are you willing to pay to own your own mind?

Most of the political wars going on today between liberal and conservative political parties is a battle over which party will control the patronage network that underpins the regime as a whole — parties that promise to dismantle power, shrink government, and unleash the free market tend to make little or no progress at the polls (with Ron Paul being the perfect example), because even though most people agree with those three priorities in theory, in practice they find ways to rationalize voting to preserve their self-interest, whether it is to protect their industry, avoid the downsizing of jobs, preserve regulatory privileges or legal cartel systems, secure government contracts, defend welfare benefits, or open the door to new government-enabled opportunities. Once you become dependent upon a system in some way, it becomes virtually impossible to vote to dismantle the ground upon which you are standing. That’s the difference between a true free market system, in which you have no control over the competition, versus a politically managed market system in which whispers, nudges, and political pressure can change who wins and who loses.

That’s the thing about the modern patronage system — many portions are informal, with many people not recognizing how their own self-interest is clouding their ability to see their own participation in that influence network as they go to the polls — the golden birdcage is still there, just more subtle than the one that existed during Louis XIV’s era. As economist Milton Friedman once said, “since the 1930s the technique of buying votes with the voters’ own money has been expanded to an extent undreamed of by earlier politicians.”

An honest politician is useful to no-one. No-one who participates in the patronage system can build a life based on unreliable privileges — if a politician’s position changes as new data or evidence emerges, then life within the patronage network becomes highly uncertain. The patronage network instinctually protects itself — and it wants stability and loyalty at all costs.

As Simon Cameron, former U.S. Senator and U.S. Secretary of War (under Abraham Lincoln), once said, “an honest politician is one who, when he is bought, will stay bought.”

The only solution is to minimize the size and reach of the political system as a whole — irrespective of whether it is a democracy, a monarchy, a feudal system, or some kind of dictatorship. The less government you have to contend with, the less incentives there are to be sucked into participating in the soul-sucking patronage system, and the greater the chance that you can build a prosperous life with your own two hands, without the winks, nudges, back-room deals, and destructive voting habits that buy privilege and opportunity inside the patronage system.

After all, despite all the pomp and prestige found within the golden birdcage, not even the king truly owns his own mind as he too is forever held hostage to playing his part in the patronage system lest his clients rise up to depose him in favor of a more amenable patron. Inside the patronage network, everyone is simultaneously both master and slave.

In The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, renowned author of Lord of the Rings, Tolkien wrote to his son that “my political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning the abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs) — or to ‘unconstitutional’ Monarchy. […] The most improper job of any man is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity.”

In the letter he goes on to say that “Give me a king whose chief interest in life is stamps, railways, or race-horses; and who has the power to sack his Vizier if he does not like the cut of his trousers.” Yet he acknowledges that this hands-off system only works as long as the world basically trundles along in an inefficient way, without someone emerging who tries to play Alexander the Great and without the factories and power-stations that have completely changed the nature of the problems facing an industrializing world.

Indeed, his seminal work, The Lord of the Rings, revolved around a quest to destroy the “One Ring to rule them all, and in the darkness bind them” (an allusion to the patronage networks that underpin political power). This master ring, representing the central authority of all-consuming power, must be cast back into the Fires of Morder by a humble hobbit, Frodo, who joins the adventure to destroy the ring with no personal aspirations of power of his own. This task to destroy the ring falls to the smallest, meekest, and most humble member of society — a hobbit — whose only ambition is dreaming of tending his garden. Anyone more ambitious who touches that ring, even with the intent of destroying it, will succumb to the temptation of using it (even for good) and thus be corrupted by its power.

But in the end, even the humble hobbit Frodo cannot let it go, and it is the greed of Gollum, the ring’s former owner who is torn between his lust for the Ring and his desire to be free of it, who snatches the ring out of Frodo’s hands but is then destroyed himself as he falls into the Fires of Mordor with the ring clutched in his hands.

Tellingly, in Tolkien’s epic story, all those who lay their hands on the ring of power, including all those who held the lesser rings of power that are subordinate to the power of the One Ring — the three elven kings, the seven dwarf lords, and the nine mortal men — are forever changed by their contact with power, reduced in some fashion to hollow versions of their former selves, bearing the weight of the world upon their shoulders. The nine mortal men were most affected of all — they were reduced to mere ring wraiths, immortal yet ghost-like wraiths bound forever to mindlessly serve as the corrupted servants of the One Ring — the perfect analogy for those who allow themselves to be captured by the patronage network. Even Frodo is left hollowed out by the experience, with a frailty and weariness afterwards that he is unable to overcome, and he is never fully able to reintegrate back into Shire life, eventually departing Middle Earth with the elves.

Three Rings for the Elven-kings under the sky,

Seven for the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone,

Nine for Mortal Men doomed to die,

One for the Dark Lord on his dark throne

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

— J.R.R Tolkien, Lord of the Rings

And so, I move on to the main purpose of this essay, to another fairy tale, this time an older one from Germany called The Rat King Birlibi, which perhaps better than any other, describes this unholy patronage system that grows up around any political system and the warping effect that it has on the mind. But first, a little context…

Prior to the 18th and 19th centuries, the German-speaking regions of Europe were absolutely brimming with fables and fairy tales, with every little valley and obscure corner of these lands having their own versions or, indeed, their own unique stories. Basically, every valley was its own Shire, except with serfdom.

But as industrialization advanced and especially as these German-speaking regions began to get bound together under larger more centralized political structures in the early 19th century, these local fairy tales began to disappear. These political changes were triggered in no small part in reaction to Napoleon marching his armies across the continent to conquer all of Europe, which accelerated the urgency to unify these German-speaking semi-sovereign micro-states into ever larger political unions and to industrialize their military systems in order to withstand the onslaught of large, aggressive, conquering industrialized armies.

While today we complain of the flattening effect of globalization on national cultures, that flattening was already well underway in the 19th century, during the emergence of large politically centralized nation states, which effectively flattened the local cultures that had thrived in the patchwork of decentralized feudal micro-states that had dominated central Europe for the past thousand years. Even in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, the pastoral simplicity of the Shire, under threat of the encroaching forces of industrialization and tyrannical centralized power, speaks to this theme.

A number of writers and publishers emerged to try to collect as many of these local folk stories as possible before they disappeared under the flattening influence of industrialization and 19th-century liberal nation-building. The most famous collectors and editors of these German fables, legends, and folk tales were the Brothers Grimm (Jacob and Wilhelm) who amalgamated more than 200 stories, collected from across the German-speaking realm.

Nor were they the only ones. A distant cousin of mine, a man by the name of Johann Karl August Musäus (1735 - 1787) made his fame and fortune by also collecting German folk stories, the most famous being the well-known legend of a capricious shape-shifting mountain spirit called Rübezahl (known as Krakonoš to the Czechs and Liczyrzepa to the Polish), collected from the historically German-speaking Giant Mountains region in Silesia, which straddles the border between modern Poland and the modern Czech Republic.

Within this heightened enthusiasm for fairy tales, which was coursing through Europe at that time, a second category of fairy tales arose — literary fairy tales written by single authors, which weren’t necessarily political but often used the fairy tale format to make social or political commentary. Authors like Hans Christian Anderson (1805 - 1875) from Denmark fit into that mold.

And so do the works of a German writer and political activist by the name of Ernst Moritz Arndt (1769-1860). It is through him that we have the story of the Rat King Birlibi, which aligns with the style of popular folk tales of that era, like those collected by the Brothers Grimm, with their moral critiques, animal characters, and grotesque imagery. However, Arndt’s stories are more polished and intentionally structured to speak to a politically aware audience — The Rat King Birlibi is a direct attack on the feudal patronage networks that sustained serfdom in Germany, which he had made his life’s mission to abolish.

A few details about Arndt’s life and complex character, and the broader context in which he published this story, really helps the story come to life. When the French Revolution broke out in neighboring France, he was initially a supporter of its ideas, especially its focus on abolishing serfdom and its desire to bring liberal democracy to France. But when the revolution devolved into the gruesome guillotine-obsessed Reign of Terror under the Jacobins, he dissociated himself and then became viscerally anti-French when Jacobin rule was immediately followed by Napoleon’s dictatorship, which unleashed Napoleon’s conquering armies onto Europe. Through his advocacy for an end to serfdom in Germany and his desire to bring democratic governance to the German people, Arndt evolved an extreme dislike of anyone who wasn’t German — particularly the Polish, Slavs, Wends (a Slavic people from north-eastern Germany), Jews, and especially the French.

Arndt, through his writing and his activism, is considered one of the driving forces that created a German national identity, and thus is considered one of the founders of German nationalism in the 19th-century understanding of that word, which emerged in response to the Napoleonic Wars and which sought to unite all German-speaking regions as a single democratically controlled nation. Nearly a century after his death, his anti-French rhetoric was recycled by Germany during both the First and Second World Wars.

Arndt was the son of an emancipated serf. Early in his life he published a scathing history of serfdom in Pomerania (the German-speaking region on the Baltic Coast where he grew up, which was then still controlled by Sweden). The picture he painted in his book was such a convincing condemnation of serfdom that it prompted King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden to abolish serfdom only three years after the book was published.

By then, most of Germany had fallen under Napoleonic rule. Arndt took refuge in Sweden and taught at a university there while championing the cause of German independence as he called for Germans to rise up and overthrow French rule in Germany. I find it ironic to discover the degree to which the later militant German nationalism of the 20th century owes its beginnings to a reactionary response to the Napoleonic conquest of German lands — the emergence of a national identity borne out of a shared sense of suffering under serfdom and under Napoleonic rule grew up over top of the highly local identities of earlier generations. As is so often the case, the emergence of a national identity owed its roots to an experience of common suffering at the hands of a common enemy.

Arndt snuck, incognito, back into Napoleonic-controlled Germany for a while to continue his activism and then traveled to St. Petersburg to help organize the final military struggle to dislodge France from German soil. Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 and exiled to the island of Elba; then, after a 10-month exile, he escaped Elba, reclaimed the throne for 110 days, and was defeated again (this time permanently) at the battle of Waterloo in 1815 by an invading Allied army from Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, the UK, Portugal, Sweden, Sardinia, and the few remaining independent German States (this time he was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena, where he died 6 years later at the age of 51). In the peace that followed Napoleon’s defeat, Arndt returned to Germany to teach at the University of Bonn.

Following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, the Congress of Vienna in 1815 restored feudal monarchies to power in all the territories that had been conquered by Napoleon, and outside of France, serfdom continued on as before. Arndt immediately began to ruffle German feathers with his criticisms of the German monarchical system, his demands for freedom of the press, and his demands for political reform to dismantle feudal privileges, promote equality under the law, and replace feudal absolutism with constitutional governance that would allow greater political participation and accountability.

Alarmed by the nationalist sentiment that was rising up across German-speaking lands to challenge centralized monarchical rule and fearful of losing control over an increasingly agitated population, Prussian authorities arrested Arndt as a revolutionary agitator during their 1819 crackdown against liberal and nationalist movements, confiscated his papers, and banned him from working in his professorship, though he was allowed to keep his professor’s stipend.

During this next 20-year period, he turned to writing folk tales, often full of moral quandaries and often with a subversive political commentary buried in the subtext. The Rat King Birlibi stands among his best — it’s the perfect analogy for criticizing the feudal patronage networks still thriving in Germany at that time, though it’s no less relevant to any other patronage system, including those that support our modern increasingly undemocratic liberal democracies.

In 1840 (at the age of 69), his professorship was reinstated and in 1841 he was chosen to serve as the rector of the university. By 1848, growing public anger against the feudal monarchical system boiled over all across Europe, triggering a series of violent revolutions demanding democracy and an end to feudal serfdom. These revolutions broke out spontaneously in over 50 countries, with tens of thousands killed before they were suppressed — they are collectively known as the Revolutions of 1848 or the “Spring of Nations”). [ As a side note, the anti-government protests, uprisings, and armed rebellions that broke out across the Arab world in 2010, known as the “Arab Spring”, were named after the “Spring of Nations” of 1848.]

In the aftermath of the Spring of Nations of 1848, reform finally came to Germany. Feudalism was finally abolished and Germany finally got its first freely elected parliament, the National Assembly in Frankfurt, which was created for the purpose of drafting a constitution for a unified German nation-state composed of the former German-speaking remnants of the hundreds of semi-autonomous micro-states of the feudal era, previously known as the Holy Roman Empire before Napoleon’s conquering armies rolled across Europe. The seeds of the vision Arndt had fought for his entire life had finally come to fruition. At the age of 78, Arndt served as one of the 379 elected deputies in the new National Assembly in Frankfurt. He continued to write and lecture until his death at the age of 90 in 1860.

If only that had been the end of the seeds that he planted, we would probably all know his name today. Unfortunately, the seeds of ethno-nationalism that were also planted by Arndt and his fellow German nationalists during the 19th century in their quest to free the German people from serfdom, feudal monarchy, and Napoleonic French rule did not die with him. Instead, the collective sense of victimhood that emerged during that era continued to fester until it found its final gruesome outlet under Hitler’s national socialist regime in the 1930s and 40s. Hitler ended Germany’s experiment with liberal democracy and ushered in a new era not altogether different from Napoleonic-style totalitarian dictatorship in order to forcibly impose his ethno-nationalism and national socialism onto Germany and beyond. As we are finding out once again in our own woke era, cultivating a victimhood mind frame is an especially dangerous mind virus that justifies the unjustifiable, especially when it manages to latch on to political power — but that is a story for another day.

Arndt’s story about the Rat King Birlibi is wholly focused as a critique of the feudal patronage network and the flattening effect it has on the human soul — thankfully, this witty story is not tainted by any ethno-nationalist themes and so has stood the test of time.

In folklore, a rat king symbolizes society decay and corrupt tyrannical rule, and especially those who live well on the back of others. According to Wikipedia, even Martin Luther, one of the key figures of the Protestant Revolution that kicked off in the 16th century, used the metaphor of the rat king to criticize the corrupt medieval Church, finishing up a long critique with the statement: “finally, there is the Pope, the king of rats right at the top” — the rat king reference (Rattenkönig in German) was specifically designed as a barb to criticize the medieval pope’s attitude of “sponging” off people. He also referred to the cardinals as “that rabble of rats”, monasteries as “rats’ nests”, and the Anabaptist theocracy that established itself in the Germany city of Münster in 1534 as a “rats’ kingdom”.

But there’s a double meaning that makes a rat king a particularly useful analogy for criticizing any patronage system…

Medieval Europe had a rat problem. Unlike brown rats, with their shorter, stiffer tails, black rats (the species that was primarily responsible for spreading the Black Plague) have long, slim tails that can occasionally get entangled and knotted together when they live in cramped and densely populated conditions, especially as their entwined tails get matted together by sticky sap, feces, blood, or gum. Furthermore, their tails have a grasping reflex that helps them climb, which makes the problem worse.

Once their tails become knotted together, the knot doesn’t come undone, especially as the rats pull the knots tighter in their struggle, which causes bones to break in their tails. The rats become bound together, like a wagon wheel, with the knotted tails acting like wagon spokes — a grisly fate if ever there was one. Bound together, they are known as a rat king.

X-ray images of the broken bones in the rats’ tails have revealed calluses at the fractures, which demonstrate that these rat kings can survive like this for an extended period of time, suggesting that they were able to lead a successful collaborative existence. The rat king truly is the perfect metaphor for the ultimate co-dependent patronage network.

The largest-known rat king was found in Altenburg, in Thuringia, Germany, in 1828, and consisted of 32 rats — it is preserved in the museum in Altenburg and is shown in image below. In 2021, a live rat king was found in Estonia consisting of 13 rats — they all look quite healthy and well-fed in the video.

As a quick side note to debunk a false understanding about rat kings that has been circulating since Jordan Peterson related a theory about rat kings on a podcast with Theo Von, which you may have seen as it spread across the internet like wildfire at the time — his story suggests that if villagers put rats in a pit, eventually only one — the rat king — would survive by eating all the others. If this were to be repeated several times, that rat would develop a taste for eating rats and could then be released back into the wild where it would hunt down and cannibalize other rats, thus ridding the village of rats.

Unfortunately, even with the help of Grok to widen my search, I was unable to find any references to substantiate this claim — nor am I the first to have looked and come up empty-handed. It’s nothing more than an urban myth, without a factual basis. However, James Bond fans pointed out that this story mirrors an extremely similar speech given by a James Bond villain in the movie Skyfall. Oops.

So, to clarify, the feudal symbolism of rat kings has nothing to do with Peterson’s theory of learned cannibalism and everything to do with collaborative patronage networks that sustain the entrenched power of a corrupt regime.

And so, without further ado, what follows below is my translation of Arndt’s original German tale of the Rat King Birlibi.

The Rat King Birlibi

by Ernst Moritz Arndt (1769-1860)

translation by Julius Ruechel

I want to tell the story of the Rat King Birlibi, a story that Balzer Tievs from village of Preseke often told me, along with many other stories.

Balzer was a farmhand who worked on my father's farm when I was eight or nine years old. He was a man of mischievous ideas who knew many stories and fairy tales. The story of the Rat King Birlibi goes like this:

In the Stralsund village of Altenkamp, which lies on the beach between Garz and Putbus, there once lived a rich farmer named Hans Burwitz. He was a tidy, clever man who succeeded in everything he attempted and who had the most well-stocked farm in the entire village. He had sixteen cows, forty sheep, eight horses, and two foals in his stables and paddocks, their coats as smooth as eels, and so well-bred that his foals were always sold for eight to ten gold coins each at the Berger horse market. He also had six handsome children — both sons and daughters — and he was so well off that people used to call him the Rich Farmer of Altenkamp.

But this man lost all his fortune because of his nighttime wanderings in the forest.

Hans Burwitz was also a skilled hunter; he had a particularly good nose for hunting foxes and martens, and therefore often spent nights in the forest where he set his traps and waited for his catch.

There, inside the forest, he saw and heard many things in the darkness and twilight and moonlight that he was reluctant to speak about, as many strange and peculiar things happen in the forest at night. It was from him that people learned the story of the Rat King Birlibi.

In his childhood, Hans Burwitz had often heard stories about a Rat King who wore a golden crown on his head and ruled over all weasels, hamsters, rats, mice, and other such skittish and scurrying creatures. This Rat King was a mighty forest king. But Hans had never wanted to believe it. For many a year he had wandered through the forest, hunting foxes and martens and setting traps for birds, but had neither seen nor heard the slightest trace of the Rat King.

However, the Rat King must have been operating in another region, for he has many castles in all the lands beneath the mountains and moves to a different castle almost every year, where he amuses himself with his courtiers and ladies-in-waiting. Indeed, he lives like a very distinguished lord, and neither the Great Mogul nor King of France could have had better days.

And don't think that this Rat King and his friends ever let nuts, wheat grains, or milk touch their lips — no indeed — sugar and marzipan are their daily food, and sweet wine is their drink, and they live better than King Solomon and the Assyrian General Holofernes.

Now, Hans Burwitz went into the forest again one night after midnight, on the lookout for foxes. From a distance, he heard a cacophony of shrill, discordant noises, and above it all, a clear voice kept ringing out: Birlibi! Birlibi! Birlibi! This reminded him of the tale of the Rat King Birlibi, which he had often heard, and he thought to himself, “I’ll go see what’s going on!”, for he was a bold man, unafraid even in the pitch-black night.

He was already about to head toward the sound when he recalled the proverb: “Stay away from where you have no business, and you’ll keep your nose.” But the calls of Birlibi continued to echo in his ears as long as he was in the forest. The next night, and the third night, it was the same. Yet he remained undaunted and said, “Let the devil and his rabble carry on their wild antics as they please! They can’t harm someone who doesn’t meddle with them.”

If only Hans had stuck to that resolve! But on the fourth night, his curiosity overpowered him, and he truly fell into the wicked snare.

It was Walpurgis Night, and his wife had begged him not to go into the forest on that wild night reserved for unholy things, for it was not safe, and all the sorcerers and weather-witches were about, capable of doing him harm, for on this night, when the entire infernal host was unleashed, many a Christian soul had come to grief.

But he laughed at her, calling it womanly fear, and went his usual way into the forest after the others had gone to bed. But that’s when King Birlibi’s draw became too powerful to resist.

At first, that night in the forest was much like the previous ones: there was a distant tumult and clamor, with the cries of ‘Birlibi’ ringing out clearly amidst it all. The whistling, whirring, and rustling above his head in the treetops didn’t trouble Burwitz much, for he didn’t believe in witchcraft at all. He said they were only night spirits that frightened people because they were unknown, mere illusions and trickeries of the darkness that could do no harm to someone who didn’t believe in them.

But when midnight struck and the bell tolled twelve, a wholly different sound of ‘Birlibi’ emerged from the forest, making Hans’s hair stand on end and tingle, and he wanted to run away. But they were too swift for him, and soon he was caught up in the midst of the king’s entourage, unable to escape.

For when the clock struck twelve, the entire forest suddenly resounded as if filled with drums, kettledrums, flutes, and trumpets, and it became bright within the forest, as though it was illuminated by thousands of lamps and candles. It was, in fact, the grand high festival of the Rat King, and all his subjects, followers, men, and vassals had been summoned to celebrate it.

All the trees seemed to rustle, all the bushes to whistle, and all the rocks and stones to leap and dance, so that Hans became terribly afraid. But when he tried to flee, so many animals blocked his path that he could not get through and had to resign himself to staying where he was. There were foxes, martens, polecats, weasels, dormice, marmots, hamsters, rats, and mice in such countless numbers that it seemed they had been gathered from the entire world for this festival. They ran, jumped, hopped, and danced wildly amongst each other, as if crazed; they all stood on their hind legs, carrying green boughs of arbutus in their front paws, and they shouted and roared and howled and shrieked and whistled, each in their own way.

In short, the whole thieving rabble of the night was assembled, creating a hideous clamor, clanging, and tumult all mixed together. In the air, it was just as wild as on the ground; owls, crows, screech-owls, eagle-owls, bats, and dung beetles flew chaotically about, proclaiming the joy of this great day with their shrill, screeching throats and their buzzing, whirring wings.

As Hans stood frightened and bewildered amidst the tumult, commotion, and clamor, not knowing which way to turn, behold, a brighter light suddenly flared up, and thousands of voices sang together in a terrifyingly ghastly solemnity that echoed through the forest, making Hans’s heart tremble in his chest:

Open up! Open up! Open the gates!

And come here from all places!

You are all invited at once;

The king is marching through his kingdom.

I am the great Rat King.

Come to me if you lack anything!

My house is made of gold and silver,

I measure money by the bushel.

And so it continued in solemn and slow song, punctuated by piercing, shrill voices shrieking Birlibi! Birlibi! in a repulsive tone, with the entire throng echoing Birlibi! so that it resounded through the forest. And it was the Rat King himself who came forth in procession.

He was monstrously large, like a bullock, seated in a golden chariot with a golden crown on his head and a golden scepter in his hand. Beside him sat his Queen, also wearing a golden crown, so fat that she gleamed. They had their long, bald tails entwined behind them, playfully intertwining them, for they were in a very merry mood.

These tails were the most repulsive sight of all; but the King and Queen were ghastly enough themselves. The chariot in which they rode was pulled by six gaunt wolves, baring their teeth, and two lanky cats stood as footmen at the rear, holding blazing torches and meowing horribly. Yet the Rat King and Queen showed no fear of them; they seemed to be mighty lords and rulers over all. Twelve swift drummers marched ahead of the chariot, beating their drums. These were hares, who must beat the drums to inspire courage in others, for they themselves have none.

Hans had already been frightened enough; but now, seeing the Rat King and the Rat Queen, along with the wolves, cats, and hares all together like this, his skin crawled over his entire body, and his usually brave heart nearly faltered, and he said to himself, “The devil himself can stay here longer, where everything goes so against nature! I’ve read and heard of wonders, to be sure, but they always had some natural order to them. But this is a motley devil’s game and a pack of fiends. If only I could get out of here!”

Hans made one last attempt to push his way out, but the procession surged relentlessly through the forest, and Hans was swept along with it. They continued until they reached the outermost edge of the forest. There, out in an open field, stood hundreds of wagons laden with bacon, meat, grain, nuts, and other foodstuffs.

Each wagon was driven by a farmer with his horses, and the farmers carried sacks of grain, bacon, hams, sausages, and whatever else they had loaded, down into the forest. When they saw Hans Burwitz standing there, they called out to him, “Come! Help carry!”

Bewildered, Hans went over and helped unload and carry with them, so confused that he scarcely knew what he was doing. In the twilight, it seemed to him that he recognized familiar faces among the farmers, including the village headman from Krakvitz and the blacksmith from Casnevitz. But he gave no sign of recognition, and they acted as if they were strangers.

The truth about the farmers was this: they had pledged themselves to the service of the Rat King and his followers, and on Walpurgis Night, when the Rat King’s great festival took place, they were obliged to transport the plunder that the Rat King’s subjects had pilfered and stolen from all corners of the world into the forest.

Hans, entirely innocent, had stumbled into this and didn’t know how. As soon as the sacks and other goods were carried into the forest, the wild thieving rabble pounced on them, and with cries of Grips! Graps! and Rips! Raps!, they each grabbed what they could and dragged it away, faster than the eye could follow, until less and less remained.

The King, however, still stood there in his grand and splendid chariot, with some still dancing, roaring, and clamoring around him. Once all the wagons were unloaded, about a hundred large rats appeared, pouring gold from sacks onto the field and the path, singing as they did:

Hands here! Hats here!

Who wants more? Who wants more?

Merry! Merry! Today is going to be great,

Merry! Hands and hats full!

The farmers fell upon the scattered gold like ravenous crows, scrambling and clawing, pushing and shoving, each grabbing as much of the ill-begotten plunder as they could seize, and Hans was not idle either, eagerly snatching his share.

As they were busily at work, like pigeons tossed peas, behold, the morning cock crowed, signaling the moment when the heathen and infernal realm holds no more power on Earth—and in an instant, everything vanished as if it had been merely a dream. Hans stood all alone at the forest’s edge. Dawn broke, and he went home with a heavy heart.

But his pockets were heavy too, filled with beautiful gold, which he did not spill. His wife had grown terribly anxious that he was returning home so late, and she was alarmed to see him so pale and distraught, asking him all sorts of questions. But, as was his habit, he brushed her off with jests and didn’t breathe a single word about what he had seen and heard.

Hans counted his gold (it was a tidy heap of ducats), stored it in his chest, and for the first few months after this adventure, he did not venture into the forest.

A secret dread kept him away. But, as is human nature, he gradually forgot the Walpurgis Night and its eerie, ghastly tumult, and he resumed his fox and marten hunts under the moonlight and starlight as before. He neither saw nor heard anything more of the Rat King and his Birlibi, and eventually thought of it only rarely.

But as spring approached, everything changed. At times, around midnight, he heard the Birlibi calls ringing out across the forest again, so vividly that the faintest hairs on his head stood on end. Though he would hurriedly flee the forest, he harbored secret thoughts of Walpurgis Night. And because what people think of by day often comes back to haunt them in their dreams at night, playing and shimmering and tricking, so too did the Rat King and his nocturnal illusions appear in Hans’ dreams.

Hans often dreamt that the Rat King stood at his door, knocking, and when he opened it, he saw the Rat King in the flesh, just as he had appeared in the chariot, but now made entirely of pure gold and not as hideous as he had seemed before. The Rat King sang to him in the sweetest voice, one you wouldn’t believe could come from a rat’s throat, reciting the following verse:

I am the great Rat King.

Come to me if you lack anything!

My house is made of gold and silver,

I measure money by the bushel.

And then he came close and whispered in Hans’ ear, “You’ll come back for Walpurgis Night, Hans Burwitz, and help carry sacks and fill your pockets with ducats, won’t you?” Though Hans, upon waking from such dreams, felt both joy at the thought of the gold and a lingering dread, he would say, “Just you wait, Prince Birlibi, I won’t come to your festival!”

But it went with him as it had with so many others, and the old proverb was to prove true for Hans Burwitz as well: Once the devil has you by a thread, he’ll soon lead you by a rope.

Sure enough, as Walpurgis Night drew nearer, Hans’s desire to join in grew stronger. Yet he firmly resolved not to give in to the evil this time and went to bed with his wife on Walpurgis Eve, determined to stay put.

But he couldn’t sleep; the wagons with their sacks, the farmers, and the great rats pouring gold from sacks onto the ground kept haunting his thoughts. Unable to bear it any longer, he had to get out of bed, slip away from his wife, and run into the dark forest. And there, that second night, he experienced it all again just as he had the first time. He had brought a small sack for the gold and gathered far more than he had the previous year.

Now it seemed to him that he had enough gold, and he swore a solemn oath that he would never again give in to temptation or set foot in the forest. And he kept that oath, overcoming himself so that he did not return to the forest or take part in another Walpurgis Night, no matter how often he dreamed of Birlibi and the golden Rat King.

He did not let these temptations take root in his heart but drove them out with fervent prayer, wearying out these devilish urges until they finally left him alone.

Many years passed, and Hans was known as a very wealthy man. With his ducats, he had bought villages and estates and had become a lord. There were whispers among the people that his wealth was not honestly gained, but no one could prove it. Yet, in the end, the proof came.

The Rat King lay in wait for the poor man, over whom he had already gained some power. He was enraged that Hans had completely stopped attending his grand festivals on Walpurgis Night. And when Hans, in a moment of sinful longing, thought once more of gathering gold and forgot his evening prayer, even uttering some unchristian curses over a trifle, the Rat King and his minions were able to break through.

Hans then learned the true nature of King Birlibi’s golden game. From that time on, Hans had neither luck nor fortune in his affairs. No matter how much he toiled, he could achieve nothing; instead, things went from bad to worse, day by day.

His worst enemies were the mice that devoured his grain in his fields and barns, the weasels, rats, and martens that slaughtered his chickens, ducks, and pigeons, and the foxes and wolves that took his lambs, sheep, foals, and calves. In short, the vermin wreaked such havoc that within a few years, Hans lost his estates and farms, his horses and cattle, his sheep and calves, until he could no longer call even a single hen his own.

He was forced to leave his home and lands as a poor man, with a stick in his hand, alongside his wife and children, and sustain himself in his old age as a day laborer.

And so, Hans often recounted the story of how he had gained his wealth and risen from a peasant to a nobleman, and he thanked God for sending rats and mice as his redeemers, making him poor again.

“Otherwise,” the poor man said, “I might not have made it to heaven, and the devil would have kept his hold over me, and I would have had to dance to the Rat King’s tune forever in the hereafter.”

He also shared that gold, gained in such a strange and secretive way, carried no blessing. Despite all his treasures, he had never felt as content in his heart as he did later in his deepest poverty. Indeed, he was a more wretched man when he rode about as a nobleman with a team of six horses than afterward, when he was often glad to have just salt and potatoes in the evening.

And that brings us to the end of this essay. If you enjoyed it, please share it widely to help me grow my audience, and please consider signing up for a paid subscription of my Substack to support my work. I rely 100% on the support of readers like you.

But if you’re not quite ready to sign up for a paid subscription, perhaps you’d consider leaving me a tip in the Tip Jar on my website to help support my writing.

Thanks for reading — see you in the next one!

Share this post