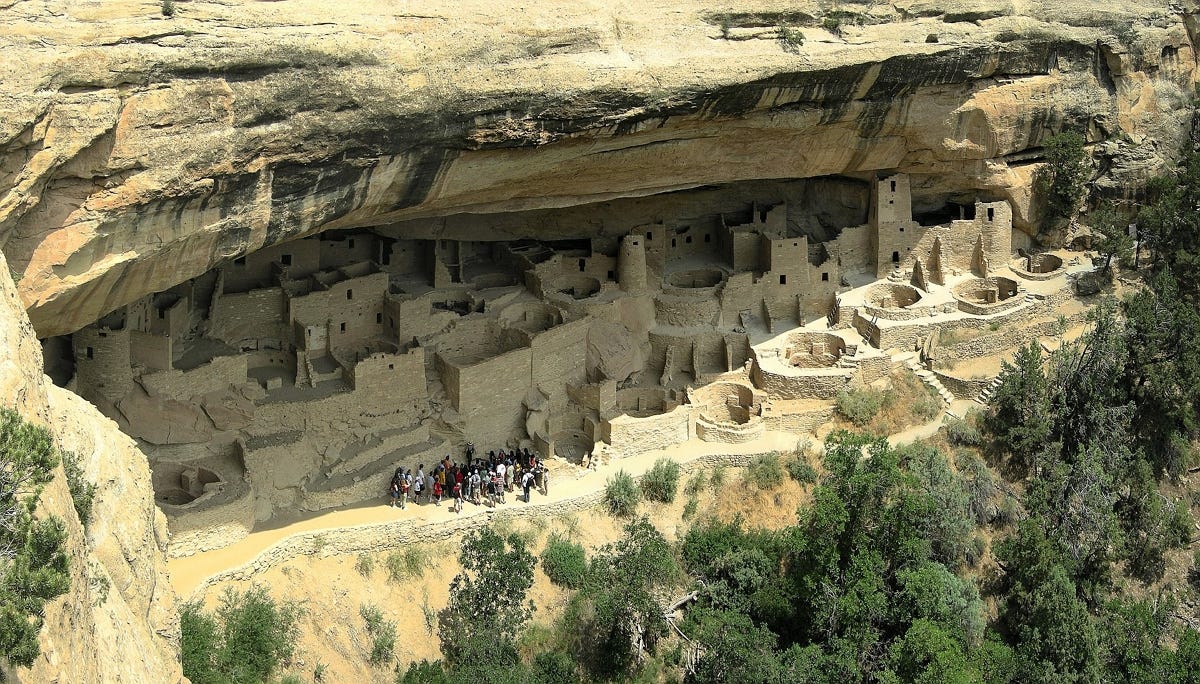

Dotting the walls of the red sandstone canyons all across the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States (where Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico meet), high up on the vertical cliffs, you can see the ancient ruins of countless cliff dwellings and granaries, big and small, perched on seemingly impossible narrow ledges, sometimes hundreds of feet up off the valley floor where the slip of a single footstep means certain death. No sane individual that loves their children would voluntarily choose to raise a family in a place like that.

And yet, for more than a century, the refugees of a failing civilization did just that.

And then they mysteriously disappeared from the region altogether, leaving behind a devastated ecosystem that even today, more than 700 years after their passing, still hasn’t recovered.

Their story is a lesson to us all — and not for any of the reasons that you typically hear on the six o’clock news.

For centuries, the Anasazi or Ancestral Puebloan culture of the Southwest divided their time between the adobe pueblos and agricultural fields that they built among the pinyon pine and juniper woodlands up on top of the cooler mesas and growing crops and building pueblos alongside reliable water sources down on the hot canyon floors. But then, in the 12th and 13th centuries, all across the region, something big changed to cause these ancient people to start moving into these precarious stone hovels perched on the edge of certain death, half-way up between the canyon bottoms and the rim of the mesas above.

What made them abandon their earlier customs to adopt such a perilous new way of life?

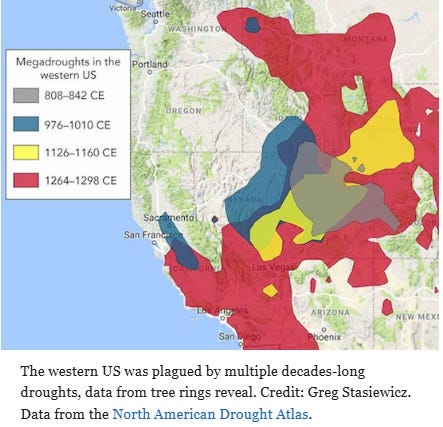

The simplistic but only partially true explanation is that the climate changed. Two brutal multi-decadal megadroughts in the 12th and 13th centuries triggered a collapse of the cultures and traditional ways of life across the entire region — the geographic extent of these two droughts is shown in yellow (12th century) and red (13th century) in the chart below.

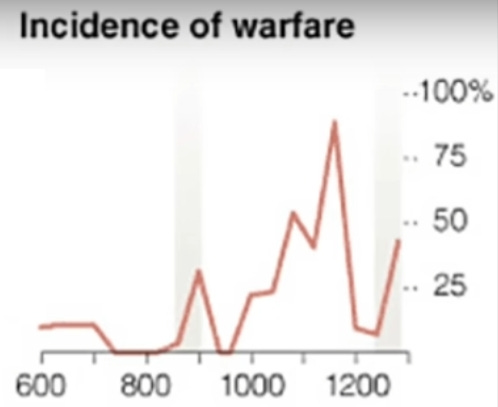

As the droughts took their toll, the entire previously relatively peaceful region was plunged into decades-long conflict, war, and extreme violence (there’s even archaeological evidence for torture, cannibalism (both ritual cannibalism and cannibalism motivated by starvation), and vicious attacks that destroyed entire villages), all of which led people to seek refuge in increasingly inaccessible places to stay out of reach of their hungry enemies.

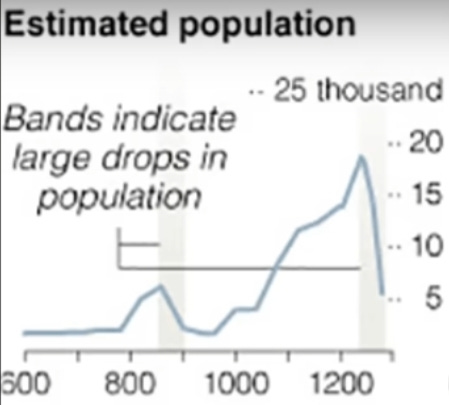

Mesa Verde in the Colorado portion of the Four Corners region is arguably the most famous cliff dwelling on the North American continent. After living primarily on top of the mesas for over 600 years, sometime in second half of the 12th century during a period of intense social and environmental instability, the Ancestral Puebloans turned Mesa Verde into a massive city. At its peak, Mesa Verde was home to many thousands of people. And yet, after nearly a century of intense occupation, by 1285 Mesa Verde was completely abandoned. The Ancestral Puebloans migrated out of the region altogether — their scattered modern-day descendants are the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, Tewa and other Pueblo peoples.

The second most famous Ancestral Puebloan archaeological site in the region (and arguably the most impressive example of ancient architecture north of the Mexican border) is Chaco Canyon in the New Mexico portion of the Four Corners region (shown in the image below). It is the largest ancient architectural complex ever built on the North American continent north of the Mexican border prior to the 19th century. By its sheer size alone, it was clearly once the core of a very large civilization. Some of its massive buildings were more than 5 stories tall and contained up to 800 rooms!

This extraordinary site at the bottom of Chaco Canyon served as the major cultural center for all Ancestral Puebloans across this vast region for more than 600 years! It was the central hub of a sphere of influence that spanned across more than 90,000 square miles (and area larger than Ireland!) and even included a huge network of roads, some more than 30 ft wide, linking together the other Great Houses across the region (more than 150 of them have been found so far), all of which are connected back to Chaco Canyon by these roads. And yet, Chaco Canyon was abandoned during the first of these two megadroughts, in the second half of the 12th century, before Mesa Verde was built and just as the mass shift to cliff dwellings in the region took place.

At its peak, Chaco Canyon’s vast building projects were supported by huge rock quarries where they harvested their sandstone blocks. They also hauled massive timbers to the site from as far as 110 km away — archaeologists estimate that more than 200,000 large timbers were transported to the site between 850 and 1200 AD using only human power (no small feat in both manpower and organizational planning considering that this is at a time before either the wheel or horses were introduced to the continent).

And the astronomical alignments reflected in their building architecture captured lunar and solar cycles that would have required generations of meticulous observations. And yet, the crippling 50-year megadrought that began in 1130 led them to abandon their canyon altogether. By 1150, more than a century before Mesa Verde was abandoned, Chaco Canyon was already an empty ruin— the central node of Ancestral Puebloan civilization collapsed during the first of those two megadroughts.

The abandonment of Chaco Canyon was accompanied by significant changes in religious beliefs and religious practices all across the Southwest. However, what emerged was not replacement by a new religion or a new culture but rather a fracturing of a large, centralized religion into less formal and more local clan-based rituals as the unifying religious authority collapsed. The large circular kivas (a.k.a. ceremonial rooms), like the enormous kiva shown at Chaco Canyon in the image above, were replaced by much smaller, less formal kivas scattered across the region. Even the rock art in the region evolved to show new motifs and evolving spiritual concerns, even as burial practices became much simpler.

In sum, we get a picture of a collapsing complex civilization that fractured into desperate and increasingly hostile rival clans, which reverted to a much simpler way of life. And where once all these people were united as a single, stable, relatively peaceful, and cooperative culture capable of building vast architectural projects and hauling timbers across the entire region, now they lived in fear of one another even as the ecosystem that once sustained them began to collapse all around them.

If you’ve followed the late Andrew Cross’ Desert Drifter channel on YouTube, which explored many of these ancient archaeological sites across the Southwest, you’ll know just how extreme the living conditions were in some of these ancient cliff dwellings that were built during that tumultuous period. These ancient people were clearly pushed to the very brink of survival and lived in terror of other clans in the region — these abandoned cliff dwellings truly capture a snapshot in time during the last stage of civilizational collapse before the region was abandoned altogether.

Complicating it all is that Athabascan tribes (ancestors of the Navajo, Apache, etc) also migrated into this region from the north, though most archaeological evidence suggests that the bulk of this southward migration of newcomers only reached the Southwest in the 1300s and 1400s (some archaeologists place the date as late as 1450 AD) long after both Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde were abandoned and after the Ancestral Puebloan population in the region had already collapsed and most had fled. So, the violence that drove the Ancestral Puebloans into their cliff dwellings was “home-grown” — the consequence of the internal chaos unleashed by a collapsing previously-centralized civilization — and is not readily blamed on the arrival of outside tribes.

But while the mega-droughts of the 12th and 13th centuries undoubtedly served as the trigger for destabilizing Ancient Puebloan culture, once you dig deeper into the geological and archaeological research (as we are about to do), you quickly discover that there is much, much more to this story.

The victims of this climate disaster were also simultaneously the chief architects of the disaster that destroyed their civilization — their impact on their local ecosystem turned what otherwise would have been just another dry period within the never-ending cyclical climate patterns of the region into an existential crisis that destroyed not only their civilization but also permanently degraded an ecosystem that was previously perfectly adapted to weather these kinds of megadroughts into the dry, fragile, brittle ecosystem that persists in the region even today.

As shocking as it may be to anyone who has toured the extraordinary wilderness of Utah’s canyonlands, although geology created these canyons, everything else about this brittle landscape was created over centuries by the mismanagement of ancient human hands.

The lessons from that long-forgotten story — about the evolution of civilization, about soil and deforestation, and about the complex forces that shape our climate and either keep our ecosystems healthy or destroy them — are all still very relevant to our own era. As Charles Lyell (the “father of geology” and close friend of Charles Darwin) famously said, “the past is the key to the future.”

~ ~ ~

If you visit any of the parks in the Four Corners region today (and I hope you do — they are an unforgettable experience!) — like Arches National Park, Canyonlands National Park, Mesa Verde National Park, Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, Hovenweep National Monument, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Chaco Culture National Historical Park, and so on — you’ll be familiar with the pervasive signs (almost as numerous as the tourists themselves) warning visitors not to step off the beaten trail onto the delicate cryptobiotic soils.

These signs are referring to the thin crust of bacteria and fungi that bind the fragile desert soil together in between the sparse tufts of grass that still manage to grow in this desert environment. In the absence of a continuous protective grass sod, this cryptobiotic crust is all that prevents wind and rain from eroding what little remains of the soil in the region.

Most people mistakenly think this is the normal soil of this desert region. And yet, in reality, this cryptobiotic crust is the soil’s last line of defense in a collapsing ecosystem because the soil itself has never recovered from the ecological collapse that accompanied the civilizational collapse of the Ancestral Puebloans — those two stories are inextricably connected.

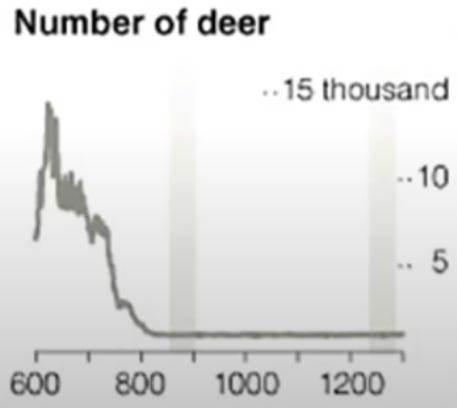

Today, you’ll see an occasional deer, antelope, desert bighorn, or jackrabbit when you visit the area. The dry cryptobiotic soils in the area simply don’t grow enough vegetation anymore to support large wildlife populations.

And yet, before the Ancestral Puebloans built their civilization, they once did.

Vast herds of pronghorn antelope and desert bighorn sheep once roamed these canyons and mesas. Andrew Cross cites an article by The New York Times in one of his videos which contains the graph below showing how deer populations in the Four Corners region collapsed between 600 and 800 AD.

This interval (600 - 800 AD) when game populations collapsed coincides with the time when the earlier semi-nomadic ancestors of the Ancestral Puebloans went through a significant cultural and architectural shift during which they transitioned from pit houses to more permanent above-ground adobe and stone structures (pueblos) and adopted a much more agriculture-dependent lifestyle based on growing corn, beans, squash and turkeys, all of which led to a substantial population increase. While hunting continued to play an important role in providing protein for the Ancient Puebloans, from that time forward their diet was heavily and increasingly dependent on their crops and their corn-fed domesticated turkeys.

Indeed, those turkeys became one of the core pillars of Ancestral Puebloan civilization. Anthropological archaeological studies describe how:

“ […] practically every pueblo had its turkey pen and that in the cliff dwellings the pen was located in the rear of the cave…Several of the early Spanish accounts mention turkeys in pens, but none of which I am aware speaks of them as running loose. Most of the pueblos were so situated that I doubt if even a Pueblo would have indulged in the labor of getting the turkeys up and down daily.”

A turkey permanently kept in confinement means that 100% of its food must be grown and stored by its owners. That requires a lot of corn! Farming clearly went from supplementing the diets of their earlier hunter-gatherer ancestors to becoming THE core activity at the heart of Ancestral Puebloan society.

As history.com reports, by the time of Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde:

“As much as 90 percent of the Southwestern Pueblo diet consisted of calories consumed from agricultural products, with wild fruits, greens, nuts and small game making up the balance. Because large game was scarce in some areas, textiles and corn were traded with the Plains people for bison meat. [my emphasis]”

Those wild empty canyons that we see today were, quite literally, once the heart of a vast agricultural civilization that relied almost exclusively upon farming for survival because the population had long since exceeded the capacity to feed itself from dwindling wild game in the region.

And as that agricultural civilization began to unravel into chaos, violence, and theft, and as their crops began to fail, those cliff dwellings became the solution, borne out of desperation, as those ancient farmers sought refuge on the inaccessible cliffs to protect themselves, their precious harvests, and their invaluable turkeys.

As a side note, turkeys were domesticated twice in North America in two separate locations — in Mexico around 800 BC by the Aztecs and in the Four Corners region around 200 B.C. by the Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloans). All turkeys today are descendent from the Aztec turkeys because the Anasazi turkeys went extinct not long after the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

However, DNA from Anasazi turkeys has helped unlock one of the mysteries of the Ancestral Puebloans — specifically, where did they go after they abandoned Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, and all the other settlements in the Four Corners region?

The oral histories preserved by modern Puebloan tribes, which today mostly live in northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico (far to the south of the Four Corners area), suggest that the Ancestral Puebloans may have migrated to the northern Rio Grande region of northwestern New Mexico (near modern-day Santa Fe) after they left the Four Corners area. But because many native tribes refuse to give permission for scientists to analyse the DNA of ancient remains, that oral history has not yet been confirmed by DNA evidence, and it is not proven whether the Ancestral Puebloans are indeed the ancestors of these modern Puebloan tribes. However, as Science Magazine reported in 2017, a group of scientists turned to studying the DNA of turkeys instead as a proxy for mapping out the migration of Ancestral Puebloans after they fled the Four Corners region.

Sure enough, before 1280, the DNA of turkey bones found in the Rio Grande area of New Mexico were purely of the Aztec variety. But after 1280, there’s a massive influx of Anasazi turkey DNA, suggesting a large influx of new people to the area who brought their turkeys with them and joined the smaller population already living in the Rio Grande region. And so, we have the first tantalizing hard evidence to support the oral histories and anthropological research which suggested that the face shapes of the modern Tewa Pueblo population of the Rio Grande area are very similar to the face shapes of the skeletal remains of Ancestral Puebloans.

But let’s get back to the main story.

Those two droughts that destroyed the Ancestral Puebloan civilization, they must have been off the charts — unlike anything seen before or since, right?

Nope.

A study of growth rings of bristlecone pines in the region revealed a much longer megadrought in the second century AD, in the midst of an already uncharacteristically dry century, which then tipped into a full-scale megadrought lasting an unthinkable 50 years. And yet, this second-century megadrought did not lead to a wholescale ecosystem collapse, it did not lead to a permanent change in the vegetation, it did not cause local wildlife populations to collapse, and did not trigger a mass exodus of people from the region.

Megadroughts are perfectly normal in this part of the world. Before the Ancestral Puebloans set up their agricultural and timber-dependent civilization in the region, the natural ecosystem of the Southwest was perfectly adapted to weather these cyclical droughts.

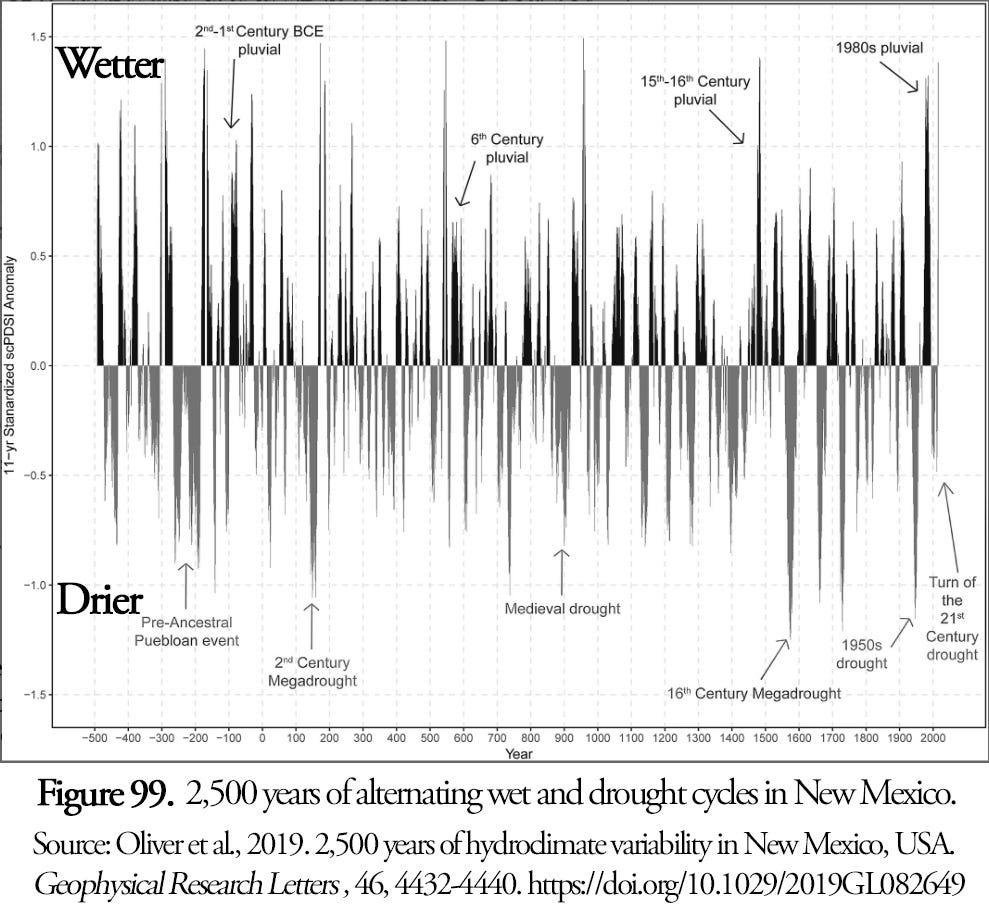

Indeed, the graph below (from my book Plunderers of the Earth), originally from a study published in Geophysical Research Letters, shows a 2,500-year history of alternating wet and drought cycles in New Mexico. Megadroughts lasting 50 to 100 years are the norm in this part of the world. The two droughts that destabilized the Ancestral Puebloan culture at Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde don’t even stand out — the 2nd century megadrought was much worse (and longer). Indeed, professor of geomorphology David R. Montgomery points out that these two devastating megadroughts in the 12th and 13th century actually fall within the range of normal climate variability for the past six thousand years! (more on Professor Montgomery’s work in a moment).

Even the modern droughts of the 21st century, which the media and climate hysterics like to broadcast as “apocalyptic”, are extremely modest by comparison with what a normal dry period in the cycle looks like over the past 2,500 years. We have been fortunate that the 21st century has been extremely mild compared to the norm — a point we should bear in mind as we consider our own impact on our local ecosystems in our own era, which have left our backyards extremely vulnerable for when (not if) the next truly dry cycle begins.

And so, when considering what happened to the Ancestral Puebloans in the 12th and 13th century, although the megadroughts were clearly the trigger, they were not the underlying cause of the civilizational and ecological collapse that followed. The key difference between these megadroughts and those that came earlier is the impact that this large populous agricultural civilization had on the land and vegetation in the centuries leading up to those two megadroughts. They made the ecosystem brittle. And then the drought came and everything collapsed.

~ ~ ~

In his eye-opening book Dust: The Erosion of Civilization (Amazon Affiliate link), professor of geomorphology David R. Montgomery describes how, despite all these earlier megadroughts, pollen preserved in the sediments show there was no change in the vegetation for thousands of years. Until the Ancestral Puebloans built their agricultural civilization. But then, everything changed.

Pollen data in the sediments and plant remains found in packrat middens in caves in the area show that once the Ancestral Puebloan culture became established, there was a dramatic and rapid change in the local vegetation as the pinyon-juniper woodlands were cut down for fuel and as ponderosa pines were harvested to provide the timbers for their massive building projects.

What today is a mix of desert scrub and grass was once woodland. If you look closely when you visit the area, you can still spot ancient stumps left behind by the Ancestral Puebloans in what is nothing but a sea of scrub and cryptobiotic soil today.

But why didn’t the woodlands grow back after the Ancestral Puebloans left the region?

Before I dive into how the Ancestral Puebloans irreversibly degraded their ecosystem to create the perfect storm when the megadroughts finally began and why their devastating impact on their local canyonlands ecosystem has been so permanent — I want to thank all my paid subscribers for your support. It means the world to me!

If you are not already a paid subscriber, I’d like to ask for your support in the form of a paid subscription to my Substack. These kinds of essays require a colossal amount of time, effort, and research to produce. My liberty to tackle topics that others cannot comes from the fact that I am not sponsored by any think tank, media outlet, or political organization. My freedom to explore ideas and think out-of-the-box comes from the fact that I am 100% reader-supported by people like you.

But if you’re not ready to sign up for a paid subscription, perhaps you’d consider leaving me a tip in the Tip Jar on my website to help support my writing.